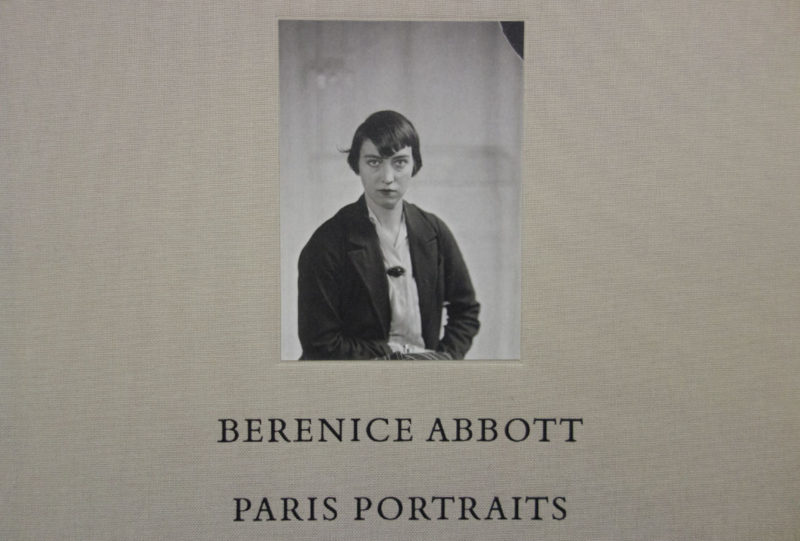

Berenice Abbott – Paris Portraits 1925-1930 is a hefty object. With a size of 9.6 x 1.5 x 12.1 inches (24.6 x 3.8 x 30.6 cm), weighing 5.2 pounds, it’s the kind of book you could drop on someone else’s table for effect. What makes it truly imposing, though, are not its physical properties. It is the photography presented inside, including the way it is presented.

As the book’s title indicates, it presents this photographer’s portrait work. Berenice Abbott might not be widely known for that. Instead, most people will probably be familiar with either her part of bringing Eugène Atget to a wider audience after his death or for her photographs of New York City. These portraits are early work. Having moved to Paris, in 1923 she started working for Man Ray who taught her how to operate a camera. A couple of years later, she started taking “occasional portraits” (to quote from testimony provided in the book). Soon enough, she followed her employer’s lead, taking people’s portraits for a small fee. That went well only for so long, and she left Man Ray’s business to start her own.

Over the next few years, Abbott photographed friends and clients, producing the pictures presented in Paris Portraits 1925-1930. Using plates, the portraits were set up to make best use of available light, and the photographer later cropped them down to the versions she kept or sold. The cropping eliminated the often messy bits around the portraits, both problems with the emulsions and elements of the room/studio itself that simply were not supposed to be seen, such as the edges of backdrops that were too small etc.

For each of the sitters, the book includes all existing portraits — 83 subjects. Presented in alphabetical order, it first shows the cropped version(s) on one spread and then the uncropped ones on the next, at their original size. Given there are between one and four photographs per person, the book’s size is determined by the need to be able to show four plates on a single page. Two spreads per sitter (plus an essay and some extra material at the end) thus results in 386 pages. I’m explicitly mentioning how the book works because I have been critical of larger productions before. Here, it makes perfect sense, even though it will probably initially confuse the casual viewer who might be confused about spreads with one fairly small picture and some text on the other page.

Of course, the book could have been produced using a smaller selection of sitters, and the inclusion of the uncropped plates might lead to some complaints as well. I don’t think the book would have gained anything from attempting to trim it down. On the contrary, it would have lost a lot. If anything, for me it’s the uncropped plates that turn Berenice Abbott – Paris Portraits 1925-1930 into the treasure it is, one of the finest photobooks I have come across this year. The cropped portraits produced by the photographer often feel too tight, boxing in those portrayed. Needless to say, commercial considerations might have been responsible for this: what sitter would want to pay money for seeing a cracked emulsion or the end of a backdrop?

It is precisely those uncropped photographs that for me make this book. I have been thinking about why that is for a while now, and I don’t have a good answer. Often, the uncropped versions just feel so much more filled with life. At times, the differences are small. But often they’re drastic. For example, there are four photographs of Lucia Joyce, writer James Joyce’s daughter. The cropped versions are good. We see a young woman posing, as if frozen in a dance, against a simple blank background. In the uncropped versions, the pictures fully come to life, though: the young woman’s body becomes impossible fragile in an environment that almost looks like is out of scale. At the same time, the environment adds an element of eccentricity that appears to darkly foreshadow her eventual long and sad descent into schizophrenia. The uncropped photographs are truly haunting in this somewhat Barthesian sense.

Berenice Abbott – Paris Portraits 1925-1930 asks to be revisited frequently. Its photographs do not offer themselves up lightly. Inevitably, there is a sense of nostalgia; and the location and time add another element of romanticism: Paris at that time — how much better can it get? But I believe that to approach the work that way takes away from the photographer’s achievement. The photographs in this book are not good just because they were taken at a great place at what in retrospect looks like a great time. They are good because an incredibly gifted artist trained her camera at those willing (or paying) to pose for her.

Very highly recommended. Essential for any serious photobook collection.

Berenice Abbott – Paris Portraits 1925-1930; photographs by Berenice Abbot; essay by Hank O’Neal; 386 pages; Steidl; 2016

(not rated)