People fall in love (and out of love) all the time. Life wouldn’t be as exciting as it can be if that weren’t the case. Our culture wouldn’t be the same without artists of all kinds contributing to re-telling that same story over and over again, without us ever getting tired of hearing it, reading it, seeing it. So there’s much to be said for photographers making work around just that, the idea of love, of falling in or out of it, of pursuing someone, getting rejected (or not).

If you got a good photobook about it, about love, you know you got something special. But most photobooks about love aren’t special, because they try so hard. Or they just wallow in cliches. And then they quickly become insufferable, at least for me, much like a Hallmark card peddling cheap sentiments. Probably the best way to get around this is to keep things as simple as possible. After all, you don’t have to do much extra work, given your viewers will make it for you, having some back story (or baggage or both) that we bring to it.

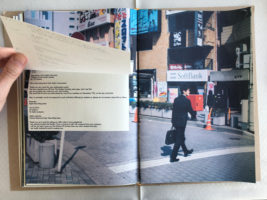

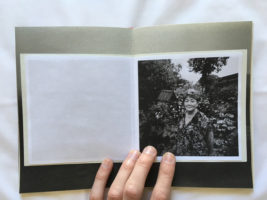

That’s why and how Thomas Boivin‘s a short story works so well. Boy meets girl, somewhere, and they meet again, and again, and then at some stage, as is often the case, one of them loses interest, for whatever reasons, or maybe the feelings weren’t quite as deep on one side. The details don’t really matter that much because it’s not a reportage or a documentary. Instead, it’s a man looking at a woman, desiring her and being infatuated by her, watching her doing all kinds of things, every one of which somehow is so important (because isn’t having a crush or falling in love just that elevation of even the seemingly most mundane detail of a person into something special?).

The book tells this story well, using text and creative layouts of a kind that of late have become a bit rare. Open older photobooks, made in the 1950s to maybe around the 1970s, to see a lot more of it, with images clearly being used in a larger (invisible) grid. The combination of text and the not necessarily tremendously exciting photographs, in combination with layout/design, make a short story work. I mean that’s the thing, you don’t need spectacular photographs for a spectacular photobook about love. Because if everything in the book adds up well, then the book is more than merely a collection of pictures.

PS: I do realize that the book is sold out and thus probably hard/impossible to get. I thought about not reviewing the book for this reason. But somehow, that felt wrong, given how good the book is. Maybe its maker will think about a second, larger edition (if he hasn’t done so already).

a short story; photographs and text by Thomas Boivin; 108 pages; self-published; 2016

Rating: Photography 3.0, Book Concept 5.0, Edit 5.0, Production 4.0 – Overall 4.1

We just had love above, and love might lead to merriment. But that’s not the only way to have a good time. Merriment can be more easily had in a variety of ways, including, of course, going to a place that promises just that, provided there is an exchange of money in return for, let’s say, drink. Just like in the case of love, there also are photobooks about bars. The OK ones cover the merriment, the better ones don’t. Instead, they focus on whatever else might be going on or might be connected to the idea of bar, and that often centers on the consequences and/or reasons for seeking out drunken merriment or even on its absence, the person’s presence in the bar notwithstanding (think Krass Clement‘s Drum).

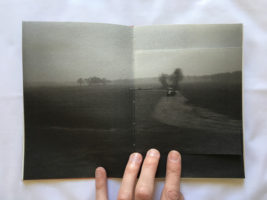

Henrik Malmström‘s Live is One Live it Well can now be added to this mix (btw, the title makes more sense if you imagine it being two lines, “Life is One,” and “Live it Well,” as it is written out on the book’s cover). Photographed in one of the grimiest parts of Hamburg, St. Georg, the book is a hefty package of photographs, which, much like the bars, require some stamina to approach. For a start, the bars depicted therein aren’t the most scenic ones. If they have seen better days, then those days are in the very distant past. Possibly, they have never seen better days at all.

With almost equal attention to (seemingly) every outlet, every cable running in the wrong place, every torn or tattered table cloth, the photographs possess a visceral power: the grime is almost rubbing off. But the book’s edit feels way overdone. As much as I appreciate many of the photographs, the book could have lost its first third completely, and that would have vastly helped the viewer. There are, after all, only so many run-down details you can look at before it gets tedious. After that first third, things become a lot more interesting, with people (literally) entering the pictures, and they interact in a variety of ways.

If there is a quiet lyricism to Clement’s Drum, these photographs offer the complete opposite. They’re almost revolting, and I don’t mean this as a negative criticism. They’re done well, but they make me not want to be there. The use of flash is harsh and relentless, and there is nothing left to imagine. Nothing. The viewer is thrown right in: “Here, deal with it!” It’s oddly mesmerizing.

Live is One Live it Well; photographs Henrik Malmström; 256 pages; Kominek; 2015

Rating: Photography 3.5, Book Concept 3.5, Edit 1.0, Production 4.0 – Overall 3.2

I’ll admit that I’ve grown weary concerning photobooks that for the first time publish work made decades ago. That’s just a mass generalization, of course. But more often than not I find that there might in fact have been a good reason for those bodies of work not seeing the light of day. No need to name any names here, whether it’s publishers or photographers.

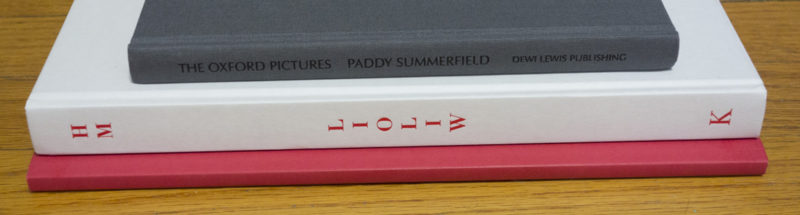

One day, Paddy Summerfield‘s The Oxford Pictures arrived in the mail, unannounced. Given it said “1968-1978” on the cover, I put it aside and looked at the other book from the same package first. That one I was looking forward to, only to have it find not quite meet my expectations. “OK then,” I thought, “I might as well look at the other one then.” Which I did, to enjoy it tremendously.

Expectations really are the pest you can’t get rid off. You’ll have to wrestle them to the ground, instead of pretending they don’t exist, especially if you engage in criticism. Of course, they do exist. Of course, this critic, much like any other one, is hopelessly flawed in a large variety of ways — that’s the way it is. So I see my job mostly not as pretending to be someone I’m not — a disinterested, objective observer, but as hoping to do a good job despite all the various problems.

I went to Oxford once, as a graduate student — what now feels like ages ago, even though it’s only twenty years. Back then, England (which I visited a lot, given that for a while I was the only member of a British research group) didn’t do much to open itself up to me. I suppose that’s just the way it prefers to see itself (as the recent Brexit has made clear yet again). It felt as if it were living of its past more than its present. It felt friendly, yet incredibly guarded, always making sure that the foreigner would know he was welcome, but aware of his proper place. You’d be welcome enough, in other words — a feeling that was strikingly at odds with the incredible generosity with which I had been treated when I had visited Scotland a few years earlier.

And Oxford just looked and felt dreadfully boring to me. Sure, there were the universities, nicely maintained lawns and all, and historical building, but that kind of history has always bored me. Take it out of its context ever so slightly, and it suddenly loses all its glory — much like an old person’s precious belongings, for example a collection of collectible spoons, that make their way into a thrift shop.

I didn’t really expect to find Oxford in The Oxford Pictures, because that’s how I prefer someone using the medium when they are an artist. I found some of it, though, in gorgeous photographs that I wish I had known before (but then I wouldn’t have had this discovery), this sense of entitlement in a setting that just reeks of beauty combined with ennui. There are a lot of students in these pictures (I prefer those photographs over the other ones by a mile — not sure what this means, but as a viewer and critic I have been craving to see faces and people of late), roughly going through the journey of going to Oxford: here, you enter, there, you graduate.

This device serves the book well, given that it provides for a structure that is simple and that doesn’t impose too much onto these pictures. These are pictures that won’t survive having too many cute or precious or smart ideas put onto them. They just need to be. And that’s good. Revisiting the book, the few pictures of doorways of details of buildings I tend to gloss over here. Maybe that’s a bit unfair, but for me, they’re unable to hold the same weight as the portraits, many of them photographed with the gentlest of touch.

The Oxford Pictures; photographs Paddy Summerfield; essay by Gerry Badger; introduction by Patricia Baker-Cassidy; 96 pages; Dewi Lewis; 2016

Rating: Photography 4.0, Book Concept 3.0, Edit 3.0, Production 4.0 – Overall 3.6