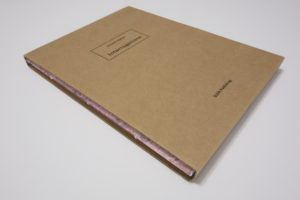

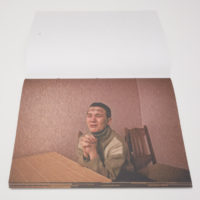

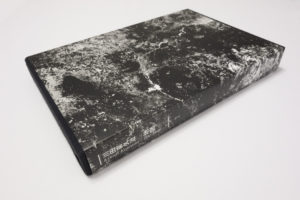

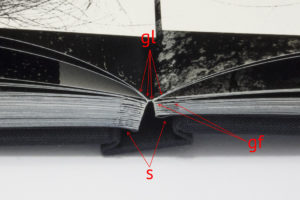

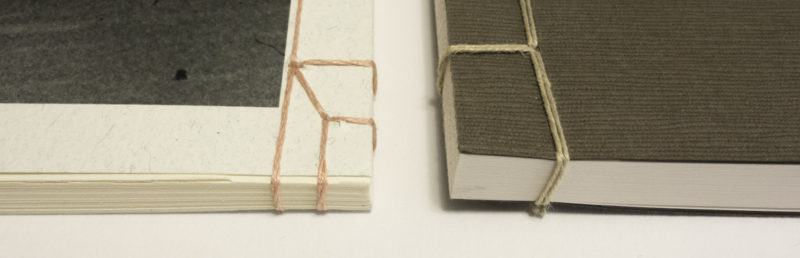

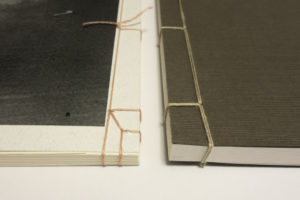

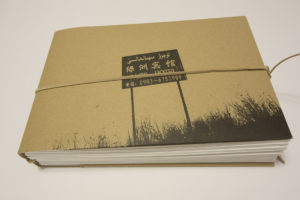

Andrzej Kramarz‘s Invisible Maps really only appears to be having a beginning and an end, because it has to. It’s a book, after all, and all books have a beginning and an end, at least as far as their physical form is concerned. There is some information concerning the book hidden inside the dust jacket. This includes the title and the colophon. There also is an essay, printed on a folded sheet of paper, included in the book (albeit not bound – it’s a loose sheet). So we are not supposed to know much. Instead, we are supposed to look and figure it out.

The idea of images working as a map of sorts is well known from Kikuji Kawada’s The Map, about which I wrote before on this site. Invisible Maps revolves around some of the same ideas, without The Map‘s extensive use of gatefolds. Unlike The Map, Kramarz’s book relies less on heavy, high-contrast abstraction, instead working with the simple fact that photographs often enough don’t reveal as much as we would like them to. This is dangerous territory to enter, given that you have to do it well for it to succeed; crucially, you have to rely on your viewers’ willingness to play along.

I’m tempted to think that Invisible Maps succeeds, but it doesn’t make it easy or simple for its viewers. If you prefer your photography to reveal itself, telling you something, without letting you hang there to figure it out yourself (in fact without requiring you to walk down the possibly wrong rabbit hole), this might not be the right book for you. I still don’t know what the hell I’m looking at here, but I’m enjoying the ride – and it gets more and more enjoyable every time.

Invisible Maps; photographs by Andrzej Kramarz; essay by Dariusz Czaja; 88 pages; Muzeum w Gliwicach; 2014

Rating: Photography 3, Book Concept 4, Edit 3, Production 3.5 – Overall 3.4

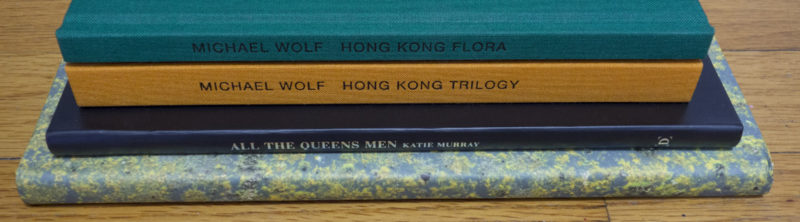

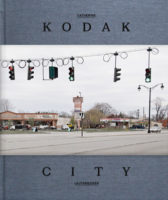

Over the past few years, Michael Wolf appeared to be content aiming for rather low hanging fruit, whether it was people flipping off Google’s Street View car or photographing the faces of people jam packed in Japanese subway trains. Make no mistake, that worked pretty well: Parr/Badger included the subway work in their latest photobook-history volume, and with online publications eager to get enough “eye balls” flashy projects are always good. But still… Thankfully, there now is something very different, something much, much better, in the form of not just one, but two books, Hong Kong Trilogy and Hong Kong Flora (there is going to be a third book coming out this fall).

Both books center on Hong Kong, looking at the kinds of details only very few people would notice, arrangements of mops or chairs or gloves or plants somewhere in the back alleys – the kinds of places you don’t necessarily go, unless you have to (because it’s part of your job). Needless to say, this description might not sound overly enticing. But the photographs do their job very well, especially given how they are put together. Hong Kong Trilogy, for example, starts out with photographs of mops, propped up or standing somewhere to dry off. How can this possibly be interesting? Well, the book shows you.

As individual images, most of the photographs aren’t that interesting (some of them are very good, though), but seeing one after the other makes the viewer appreciate what s/he is looking at more and more, to the point of wanting to go back and look again. Who knew photographs of mops could be so interesting, so much fun to look at (there is, after all, nothing wrong with fun), and, at the same time, so informative of some odd part of the human imagination?

There’s a Seinfeld episode, in in which George Costanza’s “trick” to get a date with someone is to show up repeatedly, the idea being that as annoying as the woman might find him, repeated exposure will turn him into the equivalent of some product from advertizing that you just need to have. In a sense, the pictures in these two books operate the same way. Repeated viewings of the same objects found in similar ways brings out their – and their arrangers’ – various idiosyncrasies. After a while, you don’t really want to put aside the books, given there is so much to see.

As objects, these books are done just the right way – modest in size, often with relatively small pictures inside. All in all, the photographer and publisher play a tricky game here, a game that could have gone very wrong with the wrong approach. They manage to pull it off very well. Bonus point for the following fact: the “second” edition of Hong Kong Trilogy was published in 2013, the “first” in 2014.

Hong Kong Trilogy/Hong King Flora; photographs by Michael Wolf; 152/80 pages; Peperoni Books; 2013/14

Rating (each): Photography 3, Book Concept 5, Edit 3, Production 4 – Overall 3.8

“It’s hard being a man

Living in a garbage pail

My landlady called me up, oh

She tried to hit me with a mop”

– The Velvet Underground, I Can’t Stand It

One might wonder what could possibly be interesting about making a book of photographs of men living in a completely male-dominated society like the United States. Needless to say, I’m viewing the topic as a man, albeit as one who grew up and spent the first three decades of his life in Germany. There are pretty significant differences between the US and Germany in all kinds of ways, differences that are often overlooked and/or ignored, given that on the surface the countries appear to be so similar. But dig just a little beneath the surface, and things are very different. Having a rather different idea of masculinity, I’m often surprised what American men appear to think they have to conform to, as a consequence of which, just to make this very clear, the American society looks and feels a lot more patriarchic (and violent) to me than Germany’s (which, obviously, is bad enough).

So when I saw Katie Murray‘s All the Queens Men, that was the first thing that came to my mind. On the surface, the book mostly portrays men, to be precise men living in a very particular part of New York. But I do think by extension, the books can also serve as a portrait of the various consequences of those men’s behaviour, regardless of whether it is self-imposed or imposed by society — a portrait of, yes, the United States, a country that often enough showcases the same almost cartoonishly exaggerated swagger, completely ignoring the rather shaky foundations said swagger is trying to operate on. The swagger works, at least until nobody calls the bluff.

Now the question is whether All the Queens Men calls the bluff or not. I’m not sure. I want to think it does, but it’s quite subtle. Don’t get me wrong, attacking the male swagger in kind would merely result in cartoonishness in photographic form. But I do wish Murray would have been just a tad bolder. Just a tad. The photographs are good, some very much so, but they are also polite. I just wish they were a little bit less polite. After all, if you don’t want to call the bluff, you can always let it be known that you could do it.

All the Queens Men; photographs by Katie Murray; essay by Maria Antonella Pelizzari; 80 pages; Daylight Books; 2013

Rating: Photography 3.5, Book Concept 3, Edit 3, Production 1.5 – Overall 2.8