“I picked out these portraits from an archive of approximately 600,000 photographs,” Cai Dongdong writes in the short introduction to Left, Right. “The portraits on the right-hand page of the book were taken during the Republic of China government from 1912 to 1949; those on the left-hand page were taken after the founding of the People’s Republic of China until China’s reform and opening up, from 1949 to 1978.”

The photographs all show women, whether alone or in groups. The pairings were done based on ages, clothes, gestures, and poses (the amount of work going into whittling down 600,000 photographs into these pairings is hardly imaginable). The result is fascinating and bewildering in a number of ways.

To begin with, if there were differences in available photographic materials, they are not apparent (at least to this pair of untrained eyes). There is, in other words, no stark contrast between the two photographs, where the more recent one would look considerably more modern (such as if, for example, you paired a tintype portrait with a silver-gelatin print). While this fact might (or might not) be of interest for photography historians, for a non-specialist viewer the artifice of photography itself does not force itself in between the two pictures.

In any pair of photographs, the viewer will inevitably create connections between them, regardless of how cognizant they are of the fact that they’re doing it. When two photographs look very similar, the this-looks-like-that game will be played. Much like in one of those old-fashioned visual games you used to find in old cross-word-puzzle magazines where two images were presented, with a given number of differences to be identified, the closer two photographs look, the more even small differences become apparent.

However, when looking at portraits, this game changes, given that when we look at a picture of a person, we think that we look at the person her or himself. There always is that jump to the human face and to imagining something about the person. Two more or less random strangers (or groups of strangers) that look very similar set off any number of thoughts in a viewer’s head. That’s the game being played in Left, Right.

Of course, there is the added complication (if we want to use that word) that the two time periods in question refer to two starkly different political regimes in China. There also is the added fact that up until World War 2, colonial powers and occupiers played huge and typically very malignant roles in the country, whether it was European powers or, later, Japan with its gruesome colonial puppet state (and associated mass atrocities).

None of that is apparent in the pictures, though. Or maybe almost none. If you look carefully, you can detect a few “Mao uniforms”. But the photographs were matched to be visually similar, so the corresponding dress from the earlier period is very similar. This is a nifty device that cuts out easy and shallow interpretations of the historical periods based on the pictures at hand (if you prefer such comparisons, you will have to look at different historical material).

Instead, things always boil down to the individual herself. It’s very easy to forget this, but ordinary people have almost always led mostly ordinary lives in any period of history of any given country. There might have been the occasional very drastic period where that was not the case. For the most past, these tend to be very short lived, though, providing exceptions to the rule. Furthermore, even in such periods, history still tends to get written on a large scale, a scale that glosses over the individual.

Left, Right focuses on the individual. It focuses on the fact that once you eliminate surface layers — types of clothing, say, you get to realize that across different historical periods, people have mostly lived very similar lives, focusing on their loved ones and trying to assert themselves in the tiny societal bubbles they lived in. This possibly is our only chance to learn something from history, which, after all, is unfolding right in front of our own eyes: we have to realize that it’s individuals, human beings like us, who make history.

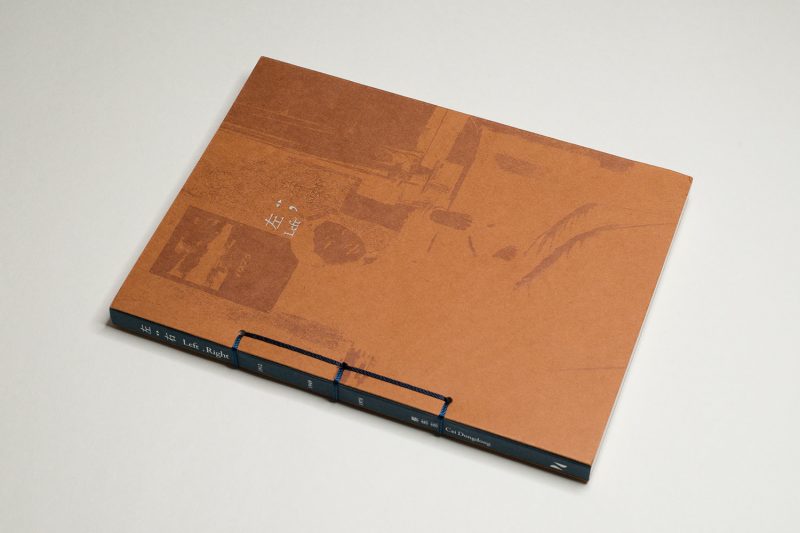

Anyone interested in book making might want to pick up a copy as well. The book uses traditional Asian binding, and its pages are very thin sheets of paper that are folded onto themselves. Given that the book centers on China, this is an obvious, yet very good choice. I’m personally a fan of books made this way: I enjoy how they feel even more like an object than regular books. This particular example is incredibly well made, down to the creation of information on the spine and the added back and front covers.

Recommended.

Left, Right; archival photographs edited by Cai Dongdong; 144 pages; La Maison de Z; 2022

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!