This year, Cortona on the Move (CotM), the photography festival located in an impossibly picturesque Tuscan village, added a photobook-dummy award to their programming. I was invited to be the juror. I spent the better part of the past week looking at the submissions to whittle them down to a shortlist, and to determine a winner.

I had previously been a juror of another, similar award; but there, the task was to pick a winner from an already determined shortlist in a jury of five. Here, though, I was in charge of everything. So I thought long and hard how to go about it. In the following, I want to share part of my process, examples of books, plus general impressions gained from looking at the submissions.

One of my pet peeves concerning photography awards, dummy or otherwise, is that shortlists often tend to be anything but short. I have come across shortlists that contain 20 entries, at times even more. I have a problem with that. It’s not only that I think a shortlist ought to be, well, short because that’s what that very word indicates. More importantly, inflated shortlists lead to the situation where the impact of every book listed is simply lessened. As a viewer, I might be interested to follow links and look at, say, ten books. But twenty? Or forty? I don’t think so.

What’s more, the moment a shortlist (or longlist) is announced, I find I get emails that point out that this or that book has just been shortlisted. I understand the impulse to share the news. But if you’re one out of forty, what discriminatory power is actually being communicated? In my grumpy moments, I keep telling people that every photobook certainly is shortlisted somewhere. While that’s hyperbolic, it’s actually not that far from the truth.

Accordingly, I decided the CotM shortlist would in fact be short, containing only five books. I made this decision without even having looked a single book, not knowing whether it would make my job easy or difficult (in the end, it made it slightly difficult).

In addition, I decided I would apply a variant of my photobook rating system. Of course, my choices would be subjective. But I needed to make sure that I would apply the same criteria for all books, even though that meant literally rating each and every entry (which ended up taking two days). In the variant of the ratings I used in Cortona, I replaced “production” with “need.” Obviously, I didn’t and couldn’t want to make the production value of a dummy a criterion, especially given that some dummies were more carefully produced than others.

But “need” struck me as being important: would this book actually have to be made? Would it add anything to the conversation? Or was it merely a rehash of something we had seen many times before? “Need” thus mimics a bit what publishers have to think about. Commercial publishers do this all the time, self-publishers might want to start doing this, given there are so many books that, frankly, nobody other than their makers need.

Before going into some of the details of the shortlist and the winner, a few observations. To begin with, I realized that the term “dummy” might mean very different things for different people. My personal opinion is that a “dummy” should simply be a prototype of a photobook. It could be handmade or commercially produced, but it shouldn’t really be published.

Various of the submitted books did not fall into that category. Unless an edition size was listed in the books I had no way of checking. So why can’t a book be self-published in an edition of 50, 100, or 300, only to then find a publisher? But then, if a book is self-published this way, why would there have to be another publisher? Doesn’t this cheapen, lessen the overall idea of self-publishing? I don’t mean to say that I have a clear answer for this, but I do think that’s an aspect of dummy awards people might want to consider.

Looking through all the books, I decided to compile a few statistics, just counting certain things that I thought I might come across. And there were indeed quite a few interesting trends. Somewhat scientific disclaimer: it’s not clear whether or not the set of submitted books constitutes a “fair sample,” whether in other words it is an unbiased subsample of all photobooks being made. In other words, I don’t know whether what I observed truly reflects the larger world of self-published or dummy photobooks.

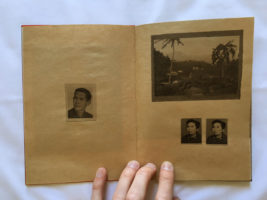

Roughly a third of the books made use of archival materials, be they vernacular or archival photographs or reproductions of non-photographic materials. That seems like a lot. While there is nothing wrong with the use of archival materials, seeing so much of it had me think it’s about time to stop what looks like a real fad to me now.

Around 15% of the books featured smaller pages or inserts. Again, there is nothing wrong with this, either. But more often than not, the reasons for doing were not very clear. Combine this trend (fad?) with the previous one, and it’s tempting to call this the Redheaded Peckerwood Effect. I quite like that book, as I’ve made clear here. But I’m not sure its strategies need to simply be adopted willy nilly in so many cases — to the point of the archival materials being a lot more interesting that an author’s own photographs, as actually was the case more than once.

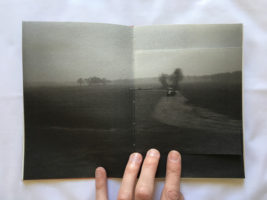

Something else I noticed only very late, without compiling any numbers. There was a paucity of human faces. Not sure what this means. But I noticed how the more books I looked at, the more I wished to see a face, and not another landscape or still life, or even someone’s hand or back, or even someone’s torso, with the head cut off.

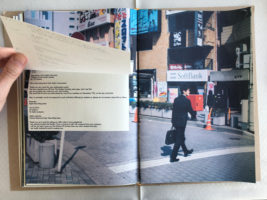

Having said all this, the shortlist I ended up picking featured (in alphabetical order) Francesco Amorosino‘s Il Libro del Comando, Hiroshi Okamoto‘s Recruit, Miyuki Okuyama‘s Dear Japanese, Carla Rak‘s Eyes as Oars, and Yulia Tikhomirova‘s Baltic.

I picked Miyuki Okuyama‘s Dear Japanese as the overall winner, a choice I was and am quite happy with. Coming home, I found out that the underlying body of work has already been published in a completely different — and as far as I am concerned vastly inferior — variation. I conferred with the festival’s organizers, and we all agreed that given the vast differences, the book would remain being the winner. It really is a great book.

I don’t know what any of my observations or comments above mean for the larger world of photobooks, especially of the self-published kind. Obviously, I have my own ideas and opinions. I will say that I am very happy with the general state of the world of photobooks. Unlike many other people, I don’t think that there are too many books. Ignoring the fact that such a judgment seems to imply there is a criterion for how to assess this. The more, the merrier.

That said, there are too many bad books, whether they’re commercially or self-published. Most books never sell their whole edition — we could take that as one, albeit not very good criterion.

I think the very first question anyone needs to ask themselves before making a book is not who will publish it or how big it should be or whether it should have gatefolds or whatever else. It should be: does this book really have to be made? Will this add something to all of these books that already exist? I felt the books in my shortlist all cleared this hurdle easily. But many of the other submitted dummies/books did not.

In other words, making a photobook for the sake of its own existence — and possibly, to increase its maker’s standing — is not a good idea. There is no gain in standing if a book essentially just adds volume to book shelves. Obviously, we could have discussions about what this really means, “does this add something”? And that would be a healthy discussion to have, a discussion that, I feel, adds a lot more value than debating about whether or not there are too many books.

(French: Un jury à moi tout seul…)