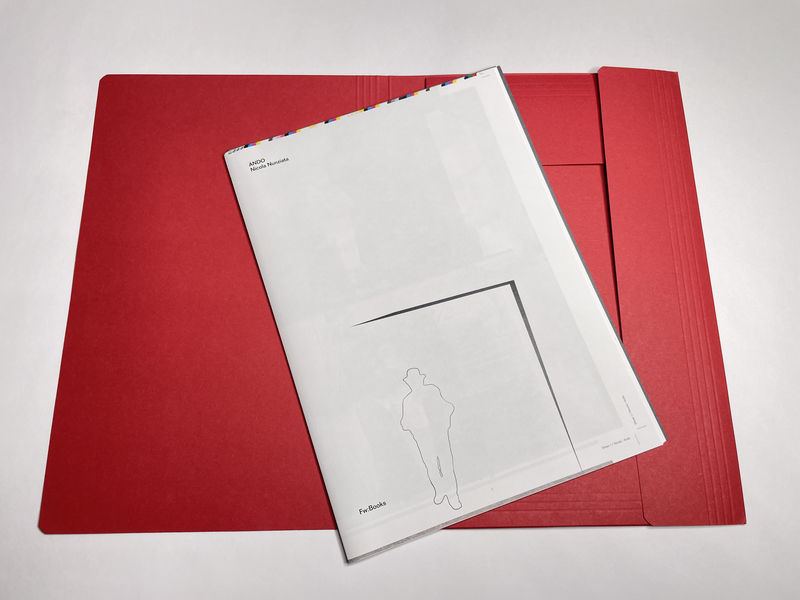

In early 2021 I reviewed Thana Faroq‘s I Don’t Recognize Me in the Shadows, a book that foregrounded the photographer’s and other people’s experiences as refugees in the Netherlands. The book left a lasting impression on me.

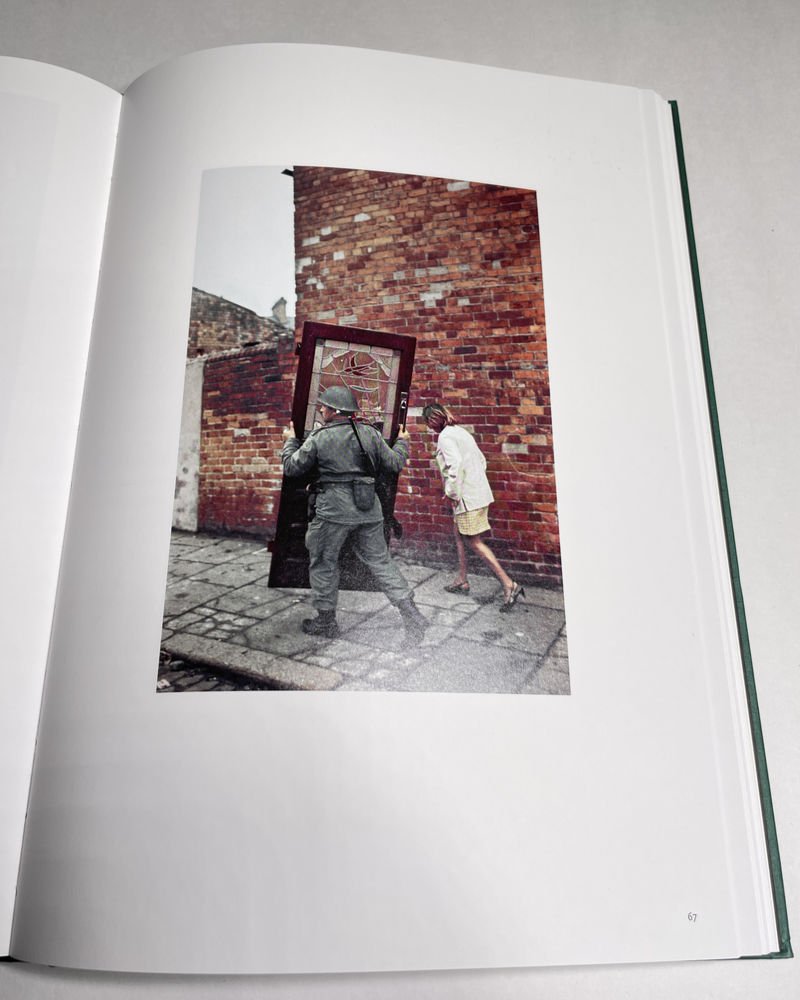

Usually, it’s photographers taking on such topics as outsiders, which might or might not lead to all kinds of problems (particularly in the world of photojournalism, which often prefers flashy images at the expense of deeper, meaningful stories). Here, the photographer was directly affected herself. In other words, the separation between photographer and subject had ceased to exist.

Late last year, Thana’s second book, how shall we greet the sun arrived, with which she yet again challenged her way of working through the inclusion of very personal writing. The combination of these two books had me convinced that I needed to speak with her to find out more about the books and the person behind it. In April, we connected over Zoom. The following conversation has been edited for clarity.

Jörg Colberg

I think it’s fair to say that a lot of people, me included, don’t really know all that much about Yemen. What would you like people to know about the country and your background?

Thana Faroq

I was born and raised in Yemen, absorbing its culture, language, and ideas. I’d like people to understand that Yemen is truly a beautiful country, despite the cliché it might sound like ‘oh my country is beautiful’. Beyond the harsh portrayals often seen in the media, there is beauty and peace. Socially, there’s a strong sense of cohesion, which isn’t usually highlighted. Being from Yemen gives me a deep sense of community. Its history is endlessly fascinating, and every day I discover something new, realizing how much more there is to learn about my culture and everything it entails. That’s what I wish more people knew about Yemen. As for the aspects I prefer not to mention, I’ll leave it to others to discover those on their own.

Jörg

I seem to remember that the country was divided into two right for a long time.

Thana

Yeah, it used to be divided into the south and the north, but that’s no longer the case since unification occurred in 1990. Occasionally, when I apply for things and need to select a country, I still see both options listed, but in reality, it’s been united. However, with the ongoing conflict, there’s a growing desire in the south to separate and become distinct again.

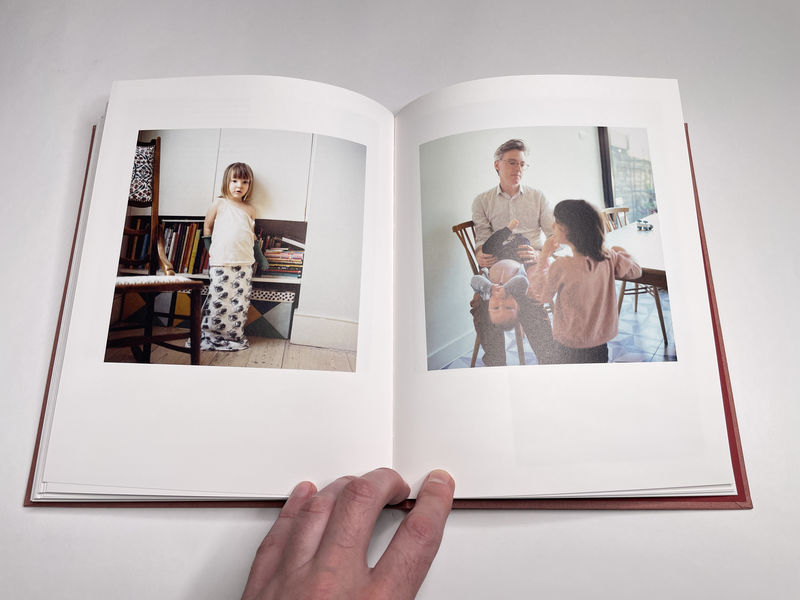

Yemen is actually what got me into photography, even though I started photography in the US during my undergraduate studies. But to be honest, it’s really hard to be a Yemeni woman and not have anything in your hands. You need to say a lot about a lot of things. Not necessarily the good things, the ones I mentioned before, but things you’re angry or frustrated about. Or you want to ask questions for the sake of asking questions. So Yemen got me into photography. We were a really small group of Yemeni women, a minority of photographers there. We weren’t many back then. For me, using the camera back then was an act of empowerment. The subject matter was not my main focus: It doesn’t matter what I photograph, but look at me, people! I’m holding the camera! That got me into photography.

I think that in a way Yemen challenges me. I hate it and love it at the same time. I never figured this relationship out.

Jörg

That is really interesting. I often tell people in the world of photography, that it’s not just the pictures. The act of taking the pictures can be very powerful. And often it’s more important than the pictures themselves. It sounds as if for you as a woman in Yemen, the camera in your hand was more important than the pictures themselves.

Thana

Definitely. I would not necessarily take selfies back then. The culture of selfies did not really exist. The camera gives me a sense of confidence. When I used to walk around the streets with a camera, I would hear: “Where’s her husband?” “Where’s her man?” “Where’s a family?” “She’s going around with a camera. Is she a foreigner?” The camera was really a protector. I am walking with a camera for a reason. It gives me the confidence. I claimed my space. And I loved it.

There were times I returned home empty-handed, without a single photo. Yet, I felt accomplished, as if I had captured something significant (not images), but their perceptions and emotions. Being a woman with a camera was enough to challenge people’s perception.

Jörg

I love that. I think photography is best where it can make people think or challenge people’s ideas. That’s so important.

Is it correct to say that you were forced to leave or that you had to leave Yemen? Maybe because of the war?

Thana

Well, how can I explain this?I left Yemen in 2016 after receiving a scholarship to study photography in London. At the time, I was quite naive, believing that the war back home would end by the time I completed my studies. Unfortunately, that wasn’t the case. I was eager to return, but then the airport was bombed, leaving me stranded. In the UK, without a valid visa or a clear purpose, I felt utterly hopeless. This prompted me to seek asylum, and I chose to go to the Netherlands. Looking back, it was definitely the right decision.

When you hear that refugees don’t have a choice I want people to believe that. No, for sure they don’t have a choice. For real. I would have definitely not left my country if it wasn’t for what happened in the world.

I got the scholarship in London, and I wanted to be equipped with what I’d learn so I could go back and keep documenting everything. But if that space is not available anymore… If the woman with the camera cannot safely walk around anymore… That was not possible any longer.

Jörg

When you had to go through the process did you meet a lot of other people with similar experiences? I think a lot of people don’t understand how difficult that process is. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Thana

It took a few months. I was lucky because it was early. Now, it is getting difficult when it comes to asylum procedures in the Netherlands. At that time, it wasn’t that difficult. We were also few Yemenis here, and the media were reporting on the war. So we had legitimate reasons to apply for asylum.

But every day felt like three years or four years. It’s not easy. It’s the waiting part, which I talked about in the first book. You are waiting. You don’t have papers. Mentally, it was not okay for me to go somewhere, even though it was allowed. But I did not do anything. What if I crossed the street and somehow missed the lights? What would happen if the police ask for my papers and I don’t have any? Mentally, it was difficult. I didn’t feel that I existed at that time. If you ask me whether I was with other people… It’s hard to remember actually. I do not even remember that I was with someone. Of course, I was with people, with lots of people. But it was me — and all the world against me. And all those people were just in the shadows.

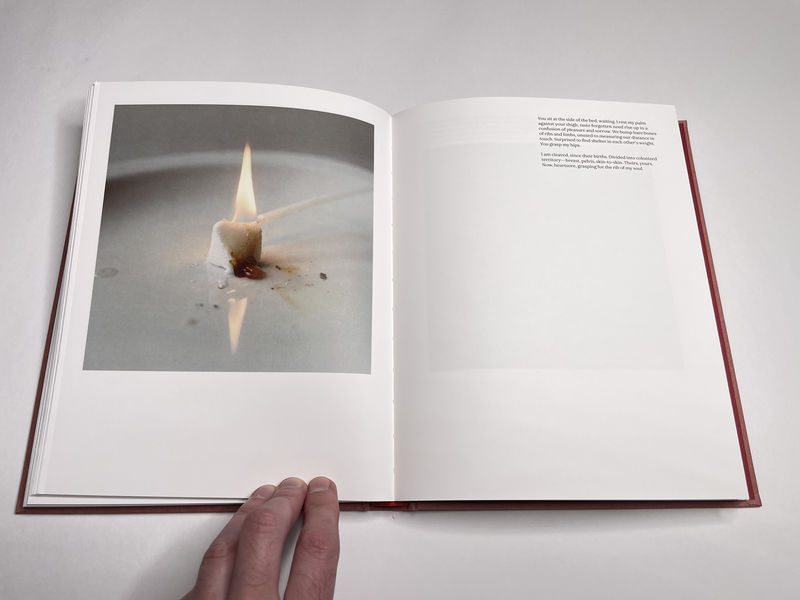

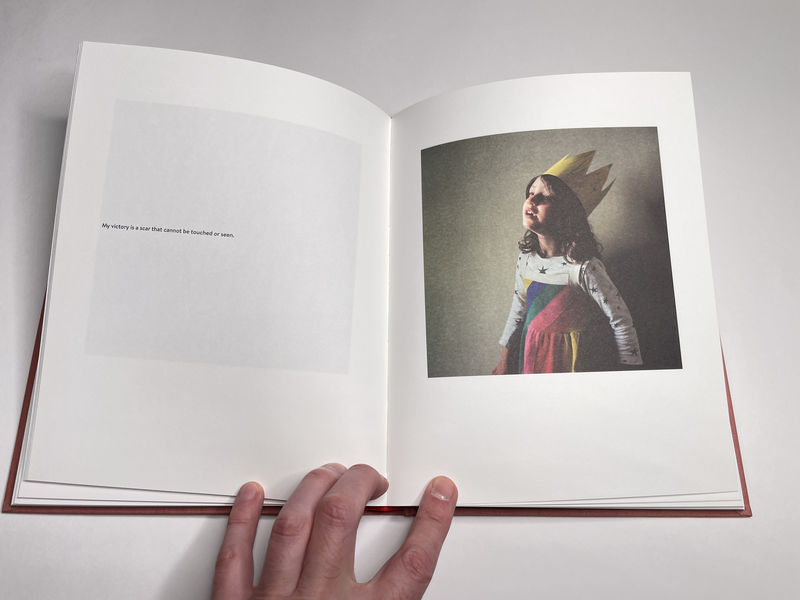

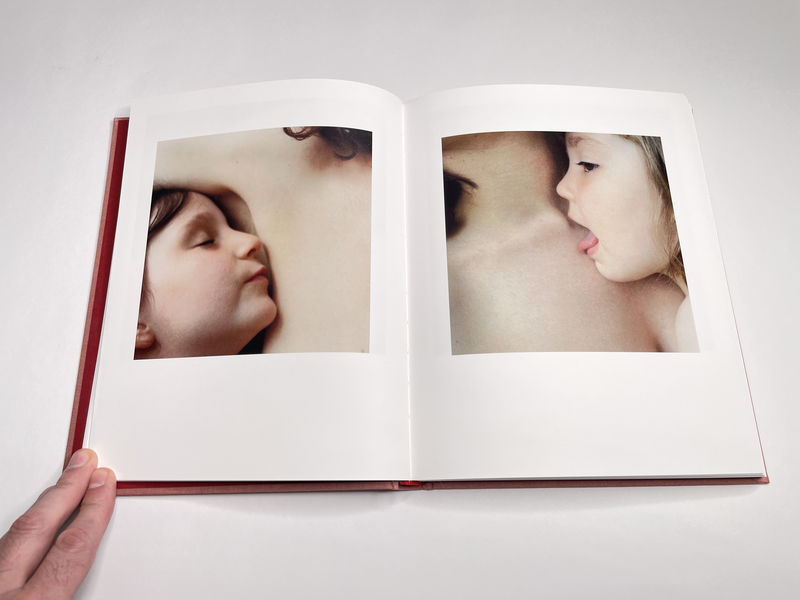

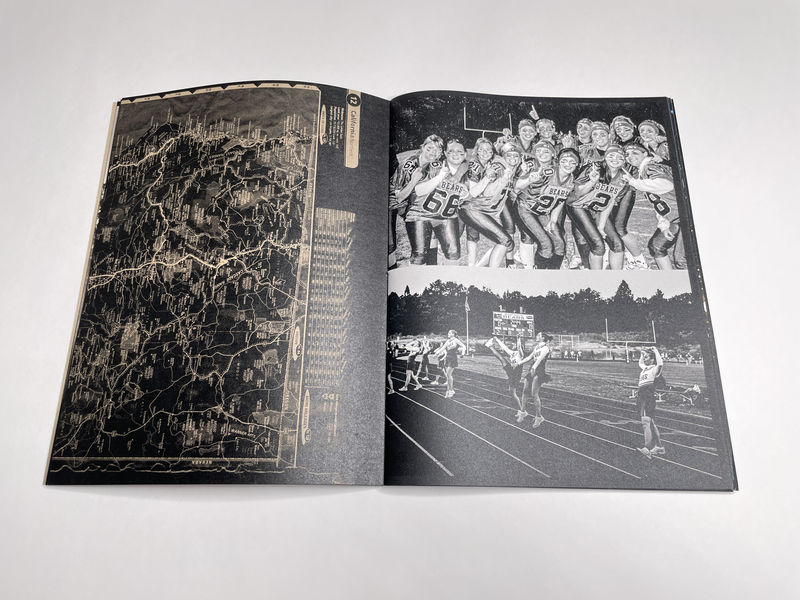

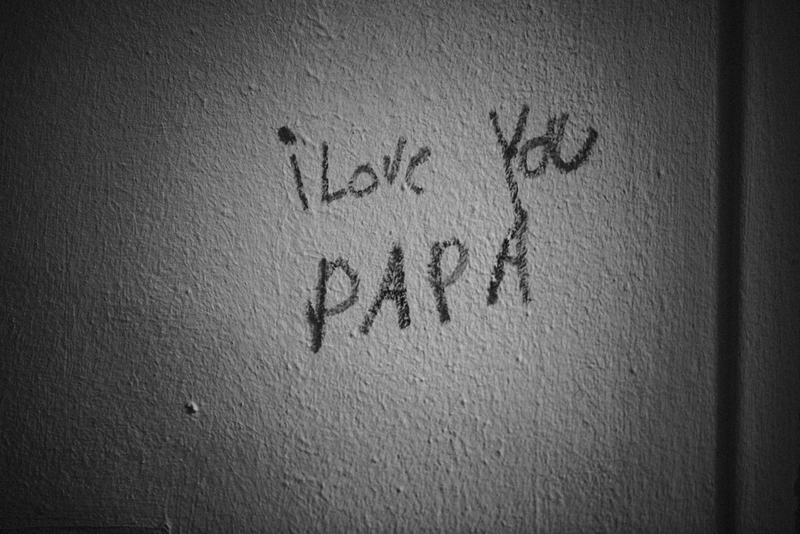

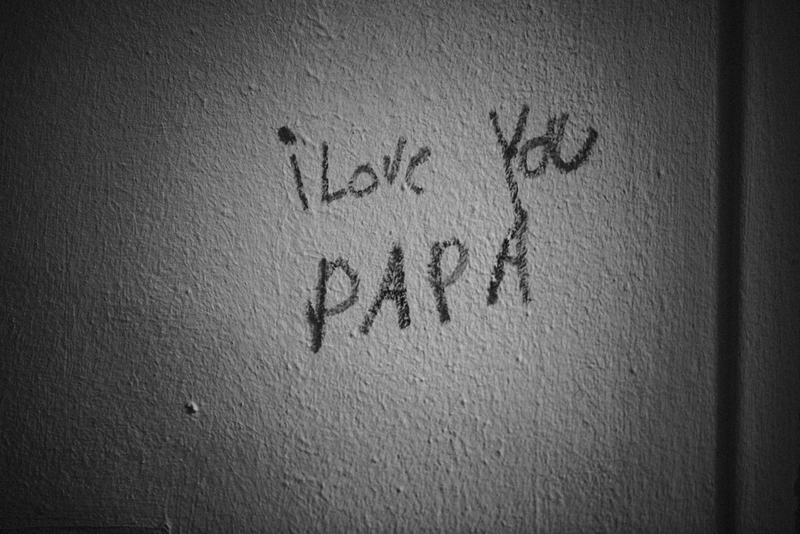

I always say this, also in the second book. We aged as women. We aged not in a physical sense, but I felt like I was 50, going through it on a daily basis, waiting… Am I gonna get the asylum papers? Am I in? Am I out? What is the situation? But somehow I used to see the light in the dark.The inspiration for my second book came from the daily gatherings with women over shisha and coffee in the camps. During these sessions, we discussed everything under the sun, love, movies, relationships, husbands, motherhood you name it… Everything, that is, except the war. These conversations have occupied my thoughts and taught me much about myself and women’s lives in post conflict and migration.

I didn’t know what resilience meant. What does it mean to say you have resilience? Is this resilience? Is it about strength? No, I was not strong. I don’t think I was strong. But it was able to endure. And I love the expression to endure in spite of it all. And of course, the camera was with me the whole time. I photographed everything.

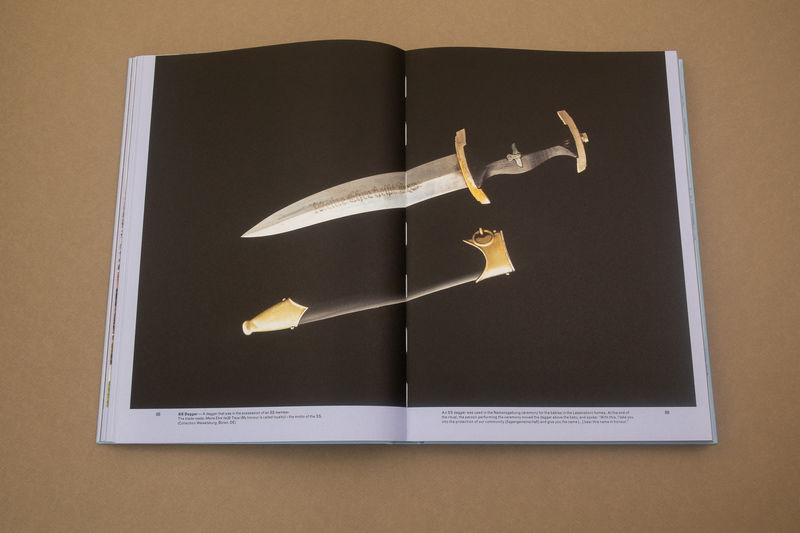

Honestly, I didn’t want my work to be interpreted as another refugee project, that wasn’t the intention ; In my work I was concerned of what was happening? Was this even real? How can I visualize trauma? Can photography do that. I’m still trying to process it all, even now. I’d be lying if I said everything was okay. It’s still a work in progress, and it likely always will be.

Jörg

Looking at your books, I think you had an idea of what photography is and what you wanted to photograph. But then the reality of your life forced you to do things differently. You started writing in the second book. I think that’s what makes the work so interesting that there is photography — and then there’s all this uncertainty around it. Am I reading something into the books that’s not there? What do you think?

Thana

You’re absolutely right, I was responding. Whenever I’m asked about my methods, I think that I work intuitively. It was about me responding to the moment. There is no certainty. There is no such thing as it needs to be photographed this way or that way. I was confronting the circumstances I experienced.

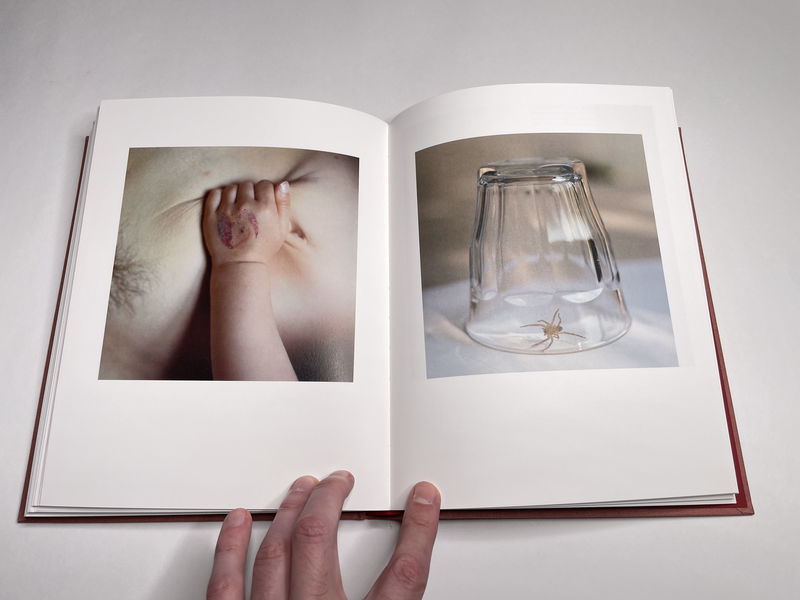

I’m no longer sure what constitutes good photography. I’d love to create work that I can confidently call good, and I aim to improve all the time. However, defining what “good” really means in photography confuses me. I find myself reacting to moments as they occur, doing my best to capture them and the feelings they evoke. Sometimes, the images let me down. The frustration of not being able to capture a feeling exactly how I envision it is immense. My work, therefore, stems both from these spontaneous moments and disappointments. These disappointments aren’t a driving force, but they shape the images I create.

The position I’m currently in, I was wondering: is photography saying enough? That’s why I started writing from a lot of frustration and not knowing what good photography is. And I always keep the viewer in mind. Will you get it when you see it? Will it have an effect on you? In the pretentious photography world, they talk about affect theory.

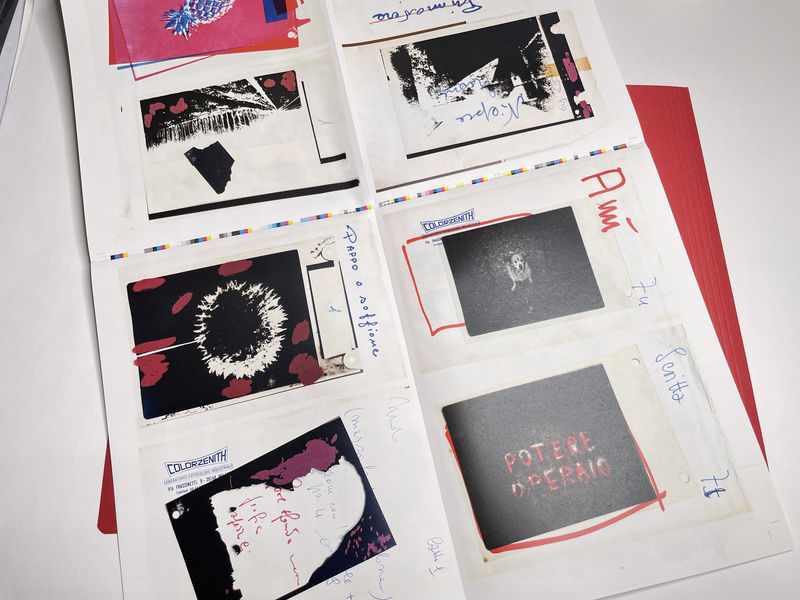

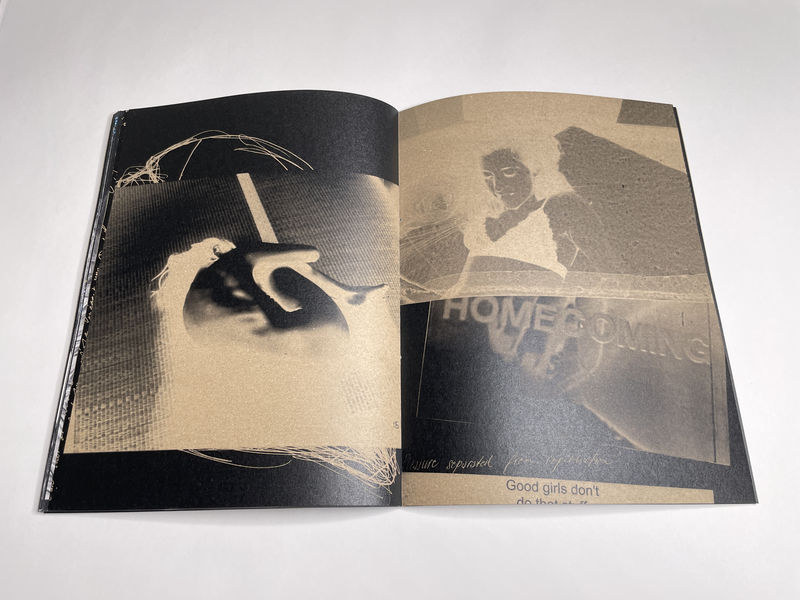

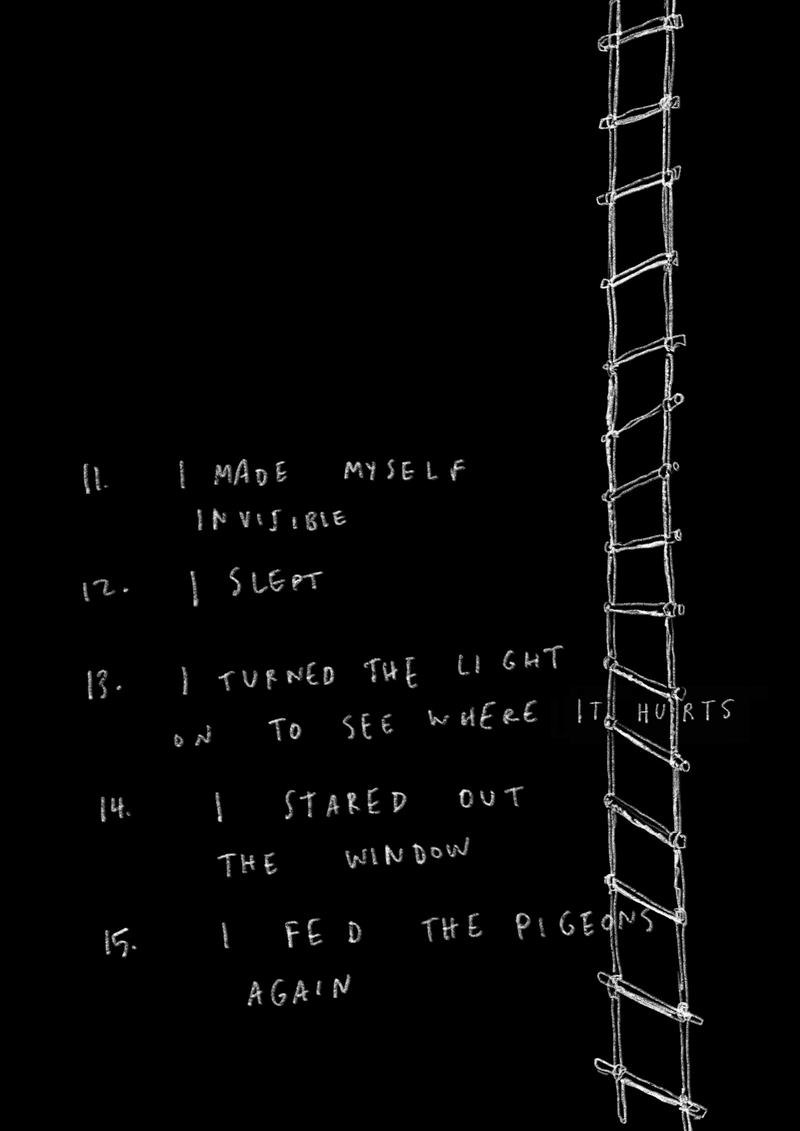

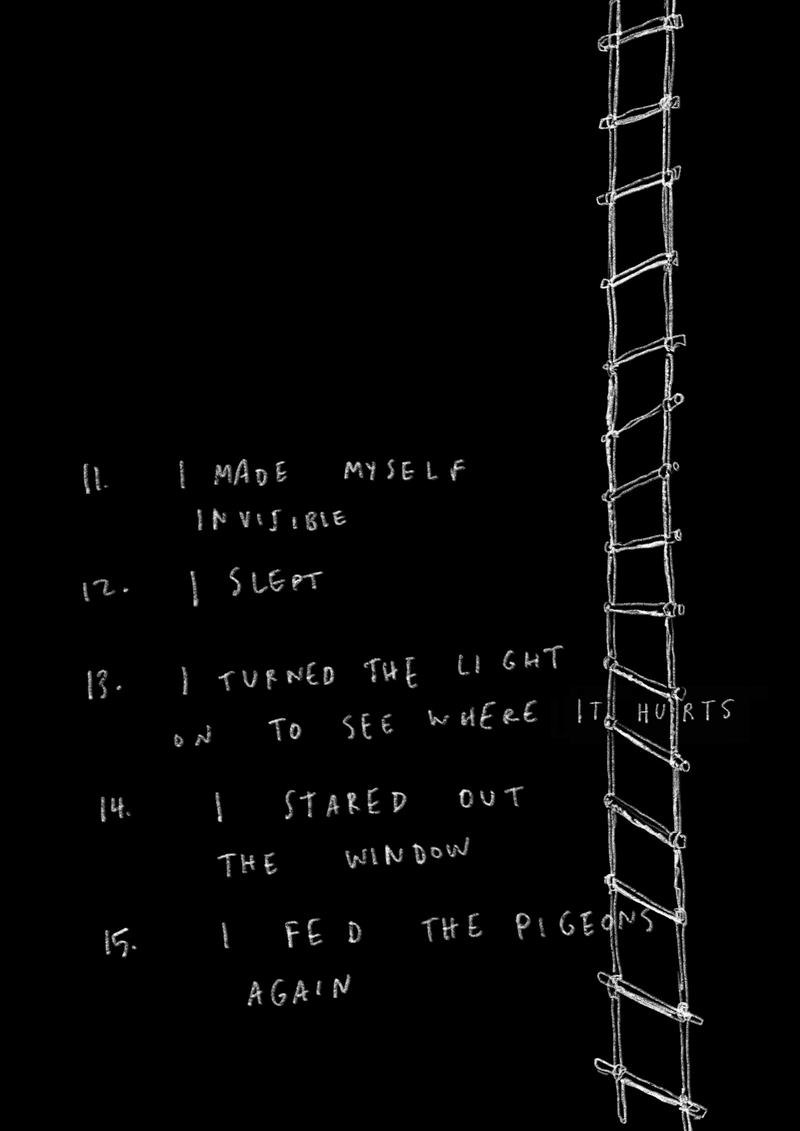

I used to question things a lot. But I stopped questioning a long time ago. Now, I think that, OK, this is who I am as a photographer. Really poor images also count. So I include poor images in the process. And you’ve seen that a lot in the first and second book: the value of poor images and how I also include them and value them.

The writing… For me, text itself can be an image. And really, it excites me to produce images through text. If something else, maybe moving imagery, will be part of the equation, I will include it too. It’s all about the moment.

Jörg

I was really fascinated when you said you included poor images. That is not something that most photographers would admit, even if they do it. And I think most people probably wouldn’t do it.

This maybe is a strange question to ask. But what do you think when you look at your books? Do they do what you hope they do? Or do you think there’s something missing and you have to make the next one?

Thana

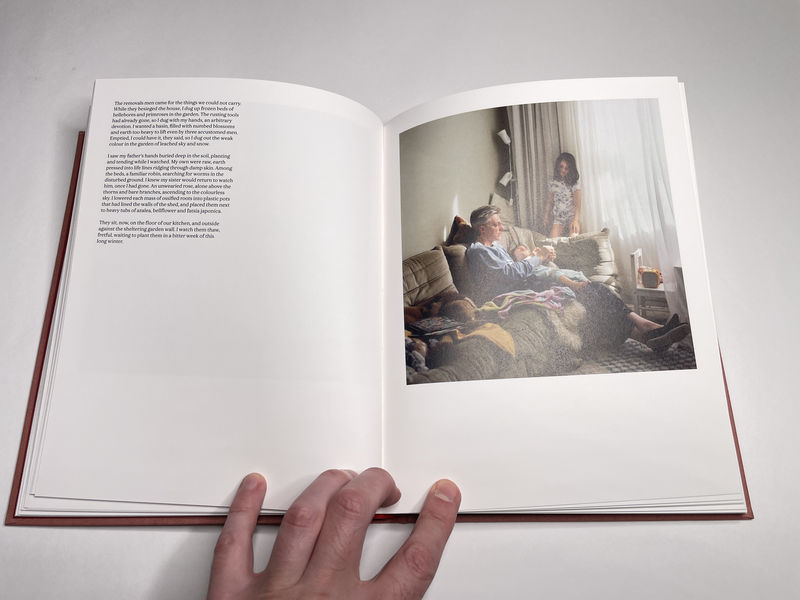

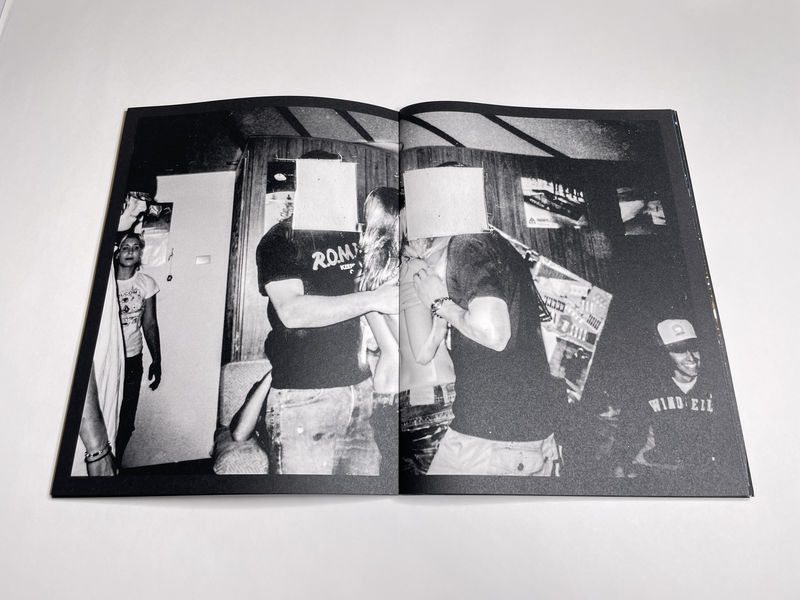

I work in chapters. The first book is chapter one. The second book is two. When I look at the two books, they are a mix of imperfection, good photographs, perfect photographs, poor images, and less poor images. It’s exactly what I need to communicate. This process, the emotional interior landscape, the landscape of whatever I’m feeling… How can I revisit trauma? What does it look like? How does it feel?

That’s also why I struggle to exhibit the work. It needs to be seen as a book because a collection of photographs on the wall doesn’t do it. You need to see it as this package with the poor images, the imperfect, the perfect. With that packaging I feel satisfied that I communicated what I needed to communicate. But there will be more. It’s to be continued. It’s happening. It’s still coming for me. I haven’t said everything.

Every story traditionally has a beginning, a middle, and an end. My fascination lies not with the start or the conclusion, but with the middle—the heart of the narrative where everything intensifies. The middle is where the chaos unfolds, where the noise is loudest. As a photographer, my method is to focus on the central part of the story. Perhaps in a few years, when you look at a collection of my works and books, you’ll notice a theme: I capture only the middle. And it’s in these middles where you find the raw, unfiltered messiness of life.

Jörg

How do your students respond? Do you tell them about poor images?

Thana

I teach at the BA level. They are still young students and excited about photography. I don’t talk about poor images. During the sequencing and editing, I don’t even say “your least favorite pictures”. But I use the term “the images you discarded”, “the ones that you left at home before coming here”. I’m really curious to see these. Why did you leave them behind?

Jörg

I have another question. This is also a difficult topic. You have residency in the Netherlands.

Thana

I have a Dutch passport.

Jörg

I didn’t know that.

Thana

I became Dutch last year. That was a really happy moment.

Jörg

Europe as a whole has a big, big problem with the far right. It’s getting worse and worse. And they’re very racist. So you just arrived at a place where a lot of people would campaign against people like you. I think that is completely shameful. How do you deal with that? And is this something that will become part of your work?

Thana

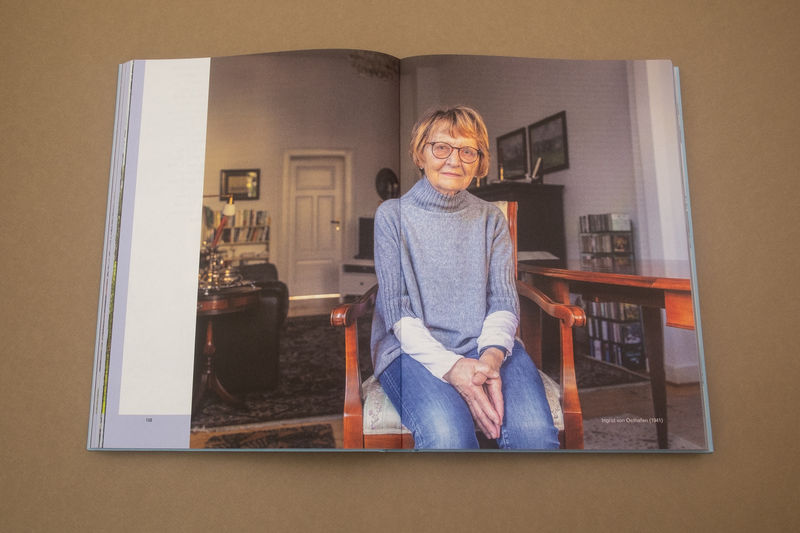

I have to tell you that when I received the Dutch passport and became a Dutch citizen, it was one of my best moments. I had asked myself whether it was it worth it, all this hardship. It was worth it. It was definitely worth it to feel that you fit in. Physically and emotionally you are part of the Netherlands. It felt really good.

When events unfolded, I came to a startling realization: what I thought was real was actually an illusion. The sense of safety and security I felt was only temporary. Now, I find myself in a place where I have to teach myself not to get too comfortable, to stay alert and prepared for change

I feel lucky because I’m surrounded by a Dutch community that is really understanding and open minded, whether at work when I teach or my surroundings in the Dutch art scene here. But the whole world is not all of it like that. So I not I’m not comfortable. That’s the word. Not scared. I’ve experienced war. I’m a war survivor. So nothing scares me anymore. But not comfortable is exactly how I feel.

Because then I’m left questioning where to go next. Last year, I visited my family in Yemen for the first time, and I must admit, I felt like a stranger both to them and to myself. If I feel out of place there, and I feel like a stranger here, where do I belong? What comes next for me? It was a deeply unsettling experience.

Of course, I will do work about that, but I wouldn’t work to… I’m not an activist. It’s not going to be the kind of work where I’m holding everyone accountable: Look at what’s happening! I will stay in my zone. I will speak about it in my own means and ways .

In my second book, ‘ How shall we greet the sun ‘ I explored the themes of integration and fitting in. Now I started a new project about what does it mean to disturb memories? The word disturbing is really really strong for me. I’m talking about the awakening and the shock and the grief that comes from it. I think I will speak about what happens when you disturb things. I plan to also address the themes of grief, shock, and discomfort. These topics will likely be explored in one of the upcoming chapters.

As I mentioned, I feel that the true value of my work will be recognized over time. My approach isn’t tied to a single project. I view my work as a series of chapters, which collectively will serve as an archive in the long run.

]]>