Photography can be art, but usually it is not. It is something entirely different. Where it attempts to be art, it has to conform to corresponding expectations, resulting in a type of packaging that even before the digital era was at odds with the medium’s central property, namely its ease of reproducibility, an ease that was grounded both in technology and people’s desires (exceptions to the rule, whether Daguerreotypes or Polaroids, do not invalidate the central point to be realized here).

Walter Benjamin wrote about some of the consequences arising from this fact against the background of the threat of fascism. Yet again, that threat has re-arrived, only to now play out in an era where vast parts of communication take place in the digital sphere: information is not tied to a carrier any longer in the sense that it was in the past. Instead, it arrives and disappears on screens of all kinds, in particular those we carry with us.

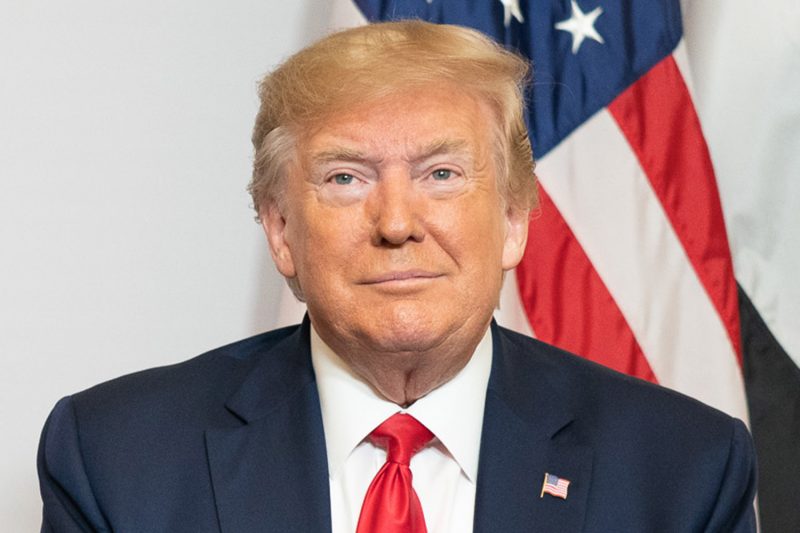

Those screens have become battlegrounds of information warfare, fueled by a variety of actors. Most famously, the 45th President of the United States is using his Twitter account as a daily exercise in narcissistic hate speech, whipping up ugly sentiments and inspiring domestic terrorists to kill those deemed subhuman.

The public sphere in which these developments play out has become intertwined with our most private one: we wake up, and we look at our smartphones to check for messages, emails, articles, and/or pictures. Pictures, however, have ceased to be just that, pictures. Instead, they have become essential elements of our communication, whether they’re emojis (which make the connection between pictures and communication most clear), photographs, or whatever else.

Pictures, in other words, have fully become important elements of our most basic communicative acts, given that to share them they do not require anything other than a device that can temporarily display them.

This unmooring of photographs from a photography-specific carrier (a “print”) has exposed the artificiality of the medium during the (roughly) first 150 years of its own existence, an artificiality driven ad absurdum by those operating with photographs in the art market.

Photographs demand to be seen, and for that demand to be fulfilled they needed to become data: This is the central aspect of the digital revolution (the ease with which pictures can be manipulated is relatively meaningless in comparison). Of course, photographs do not command to be seen on their own. It is us, their makers, who want them to be seen.

To share a photograph is a communicative act in which more often than not the actual picture in question is meaningless: it will be looked at for a fraction of a second, all kinds of thoughts might be triggered, but it will never re-appear. It could re-appear because the photograph will exist in some memory banks somewhere, but it will not be re-displayed.

When it will re-appear, it will often do just that because some corporation’s algorithm was designed to trigger a feeling of nostalgia in its users, to attempt to tie them more strongly to whatever platform they are engaged in. Beyond such machinations, however, the vast majority of photographs are looked at briefly, once. Consequently, there exist platforms which share pictures that disappear forever once they have been seen.

In the long run, most photographs are thus completely meaningless, however much meaning they might have possessed in the moment when they were shared and seen: there will always be another picture, another communicative act.

Photographs have thus more in common with money than with the kinds photographs money can buy in an art gallery: we all use money, whether in physical or digital form, but we only care for it thinking of its exchange value.

As noted above, our private communications are never very far away from the most public ones – they all end up on the small screens we carry around us and that we look at in a regular fashion. The public and the private have merged: we share parts of the latter with the former, and the former reaches us in a variety of ways: social media, the news, or whatever else.

These days, expressions of hate are never far away, whether in the form of a tweet by Trump (which we might see even if we don’t follow the man on Twitter, given that the news media still happily quote it) or by anyone emboldened by what can only be understood as a complete collapse of central parts of the idea of the US presidency (however flawed many of their ideas and approaches were in retrospect, it is hard to imagine the founders be willing to accept a complete moral vacuum at the very core of the country they founded), a comment left by someone angry (or someone possibly in the indirect employ of, let’s say, Russia’s president), or whatever else there might be.

Whatever else there might be – there’s a lot. These days, to partake in that public/private sphere that’s connected to our smartphones is to inevitably enter a cesspool of willful ignorance, hatred, and barely concealed violence. To be connected to the world these days means to partake in a racist reality TV show that runs on all channels — and we are not given a choice whether to watch it or not. It simply is there. Our lives have thus become invaded with violence of all sorts, and photographs play an essential part of that.

Before pictures became data, one would have been easily able to disengage from all the nastiness that has become such a dreadfully ubiquitous part of our daily lives now. Now, though, that choice is essentially gone.

It is true, you could still cut yourself off from most of it. But could you really go about a life of your own willful ignorance as Gestapo-style raids target immigrants or as any trip to the local supermarket or mall might end up on the coroner’s table?

If, in other words, you care for someone other than yourself, anyone really, how can you avoid caring for the larger good that in some form or another we’re all part of?

Can we, in yet other words, make pictures while pretending those pictures do not enter this particular environment we live in right now? Is there such a thing as an activist photographer?, Colin Pantall asked. I’d like to propose a re-phrasing of the question: when the private and the truly ugly public have become as enmeshed as they are now, can there be a photographer who is not an activist? Aren’t you an activist of some sort the moment you share a photograph and drop it into the larger public-private pool?

I am not convinced that in the era of Trump, which would have been impossible without the incessant digital proliferation of information, photography cannot be a form of activism. To deny it that status would be to deny the extent with which public ugliness and violence have entered our own private lives, in part because of our choices (nobody forced us to sign on to social media), in part because the choices available to us have become so relentlessly limited.

Activism here does not necessarily entail attempting to change the world on a larger scale. Sure, one could go about something to help solve the climate crisis, to help immigrants, to help bring about gun legislation (and thus give coroners a break), or whatever else.

But at its most atomic level, any photograph that is shared with someone else and that was made with elements of compassion, if not love, is already a form of activism, a push back against the aforementioned onslaught of outrage, anger, ugliness, and violence.

Maybe those of us who think of themselves as photographers or even artists need to realize that that is their medium now: a means of communication, maybe the means of communication, and if we want to mentally (let alone physically) survive the times we live in right now, there will have to be a collective push back against the ugliness that we have allowed to invade our public and private lives.

Enough is enough!

Make pictures and share them!

But make picture and share them with the intent of brightening other people’s days, of reminding people that the hatred and cruelty perpetuated by Trump et al. are their choice, not ours, a choice that we can and will reject!