Forty years later, it would almost seem to be unbelievable that one of the most important changes in photography in (then West-)Germany would result from an adult-education institution in (then West-)Berlin offering what would become groundbreaking classes (in Germany, a Volkshochschule — which literally translates as “people’s university” — can be found in most cities and town. A Volkshochschule typically offers all kinds of classes, from languages to crafts to hobbies etc.). At this current point in time, the influence of the Düsseldorf School at the art academy there is well established. Those more familiar with the history of German photography might know about Essen under Otto Steinert being the dominant school before that. How would a Volkshochschule‘s program run by someone who wasn’t even trained as a photographer — Michael Schmidt — fit into all of this?

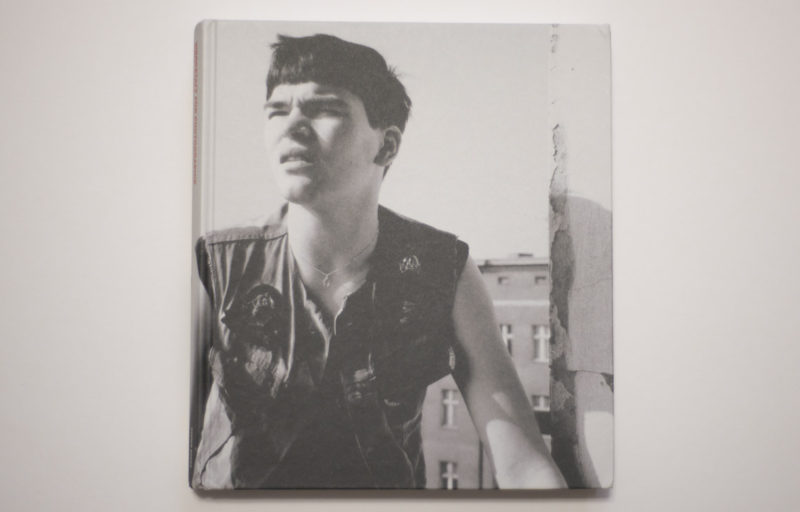

A new catalog produced at the occasion of three exhibitions running in parallel provides a first, much needed access to what might be one of the biggest topics concerning the history of German photography for the next few years: Werkstatt für Photographie 1976-1986. The three exhibitions ran at Museum Folkwang in Essen, C/O Berlin, and Sprengel Museum, Hannover under the guidance of Florian Ebner, Felix Hoffmann/Thomas Weski, and Inka Schube, respectively. These four curators also provided the main essays in the catalog.

You might wonder whether the stress on the importance of the Werkstatt might not be unnecessary hyperbole, given that in all likelihood you have never even heard of it before. A simple list of photographers who at some stage were part of the courses might help address this concern. There are Joachim Brohm, Andreas Gursky, Eva Maria Ocherbauer, Joachim Schmid, Thomas Weski, and Petra Wittmar, plus a large number of others (more about them later). Schmidt (Michael — note the Joachim one is lacking a “t” at the end of his name) invited a number of British and American photographers to either give workshops and/or show their work in Berlin, often making it the very first time for a German exhibition. Those included people like Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Larry Clark, William Eggleston, Larry Fink, Robert Frank, Lee Friedlander, John Gossage, Paul Graham, or Stephen Shore. On top of all of that, there also were occasional contacts and meetups with photographers in East Germany, however difficult those were to arrange.

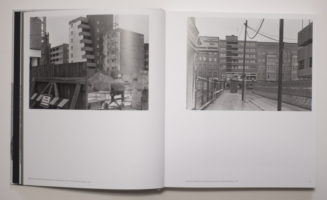

What makes the history of the Werkstatt so interesting, however, are not necessarily the lists of names provided in the preceding paragraph. Instead, there are all those photographers you might never heard of, some of whom produced work that is in serious need of re-discovery. In addition, Schmidt’s Werkstatt wasn’t just a stomping ground for what were to become famous names in the history. It also radically altered the approach to thinking about and teaching photography in Germany, bringing a lot more subjective approach to the medium, in particular concerning its documentary branch. At the risk of being a little simplistic, you can see this change in thinking in Schmidt’s own work, if you compare his early Berlin photographs (here’s an example) with something like Waffenruhe (example). That’s the same Berlin, but it looks and feels a lot different.

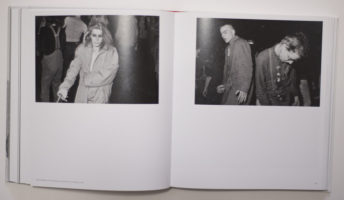

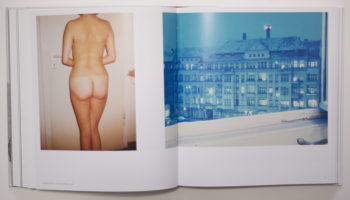

Werkstatt für Photographie 1976-1986 is organized into four sections, A Different Landscape, A Different Portrait, A Different Body, and A Different Picture. In each section, photographs from visitors are mixed with work by teachers and/or students. At times, as can possibly be expected, a German photographer might emulate the model of an American visitor, such as when, to give an example, Wolfgang Eilmes channeled his inner Larry Clark and photographed youth/drug culture in Berlin, Tulsa style. But often enough, the imitator brought a completely new dimension to work made by a famous US photographer.

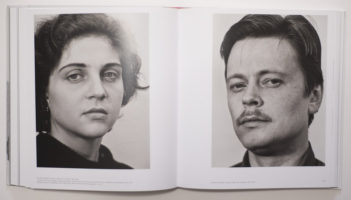

My probably biggest revelation was seeing Christa Mayer’s photographs from a psychiatric ward (Mayer worked professionally as a clinical psychologist and psychotherapist at a psychiatric clinic in Berlin). Square pictures that are clearly in tradition of Diane Arbus, Mayer’s photographs are some of the very best portraits I have seen in a long while, completely eclipsing Arbus’. Where Arbus essentially gawked at her subjects in ways that I increasingly feel are unhealthy and, frankly, tasteless, Mayer’s are infused with a deep understanding of our shared humanity — essentially everything that is completely absent from Arbus’ gawking grotesqueries. Seeing one of Mayer’s photographs brought tears to my eyes — there are less than a handful of photographs that, so far, managed to do that.

Christa Mayer is not the only photographer whose work I had never seen, despite it being so strong. There are so many others in this catalog, people like Uschi Blume, Gabriele and Helmut Nothhelfer, or Wilmar Koenig, to name just a few. As reluctant as I am to ask for more archival work to get published in photobooks, making this work available — instead of that previously unseen forgettable body of work by one of the usual suspects — sounds like a pretty great idea to me. Werkstatt für Photographie 1976-1986 is a great start, it’s the kind of catalog that I wish had even more pictures.

The book’s essays provide much needed insight into the history of the Werkstatt and the larger situation around it. Just like in the case of the pictures, I wish there was even more text. But as such, there already is so much to learn, so much to discover. In particular Thomas Weski’s essay dives deeply into the history of the Werkstatt. Given Weski was actually present in some of the courses (he is depicted in various of the photographs, but he also provided some himself), his knowledge and insight is based on first-hand knowledge (on top of what must have been a lot of work later). Weski now heads the Archiv Michael Schmidt in Berlin.

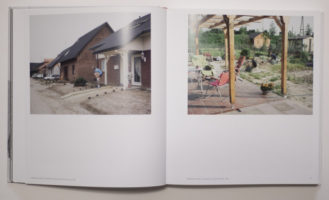

The conditions under which the Werkstatt happened are long gone. Berlin is happily reunited, and photography is again being taught under the more regular circumstances of art academies, universities, or dedicated private schools. It’s fascinating to imagine another Werkstatt somewhere in Germany, a place where photography would be studied and made in ways challenging the status quo, while being open to the medium’s many possibilities. It’s hard, very hard, to imagine it could happen. We’re lucky to have been given a view into one of the most fruitful episodes in recent German photography, those ten years when a handful of mostly Berlin-based photographers would shake up their medium.