I’m imagining these must indeed be interesting times if you are Chinese, and you see your country transform so massively. The process is unlikely to happen without producing the equivalent of what in the US are called Americana.

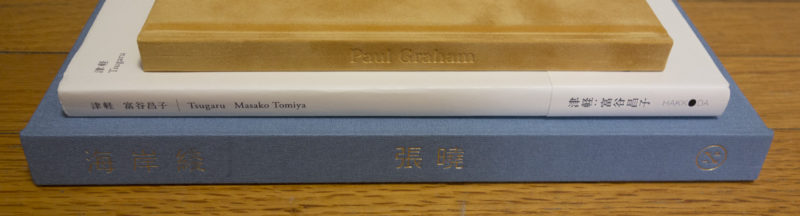

Around a decade ago, China was “discovered” by Western photographers, with a flurry of work being made there. Our attention has now moved elsewhere, which – thankfully – has opened up ways for photographers who look more carefully to present their work around China. One of them is Zhang Xiao, whose Coastline has now been released.

As its name implies, the photographer traveled along China’s coast to essentially assemble a portrait of the country. To argue over how accurate this portrait might actually be would miss its point entirely. Instead, the book invites us to view the country with very particular eyes, eyes that have a knack for finding the slightly absurd in what initially look like often very mundane scenes.

For example, in one photograph there is a young woman sitting on the grassy banks of a river. Behind her, a bridge almost crosses the river. The last 5% or 10% of the bridge are missing – construction appears to simply have stopped. So a few rickety planks finish the job. In fact, there is a man who appears to be making a decision about whether or not to walk down that very construction.

Given that the absurdity in many of the photographs is somewhat restrained, it is unlikely to cross the reader’s mind that the photographer is making fun of anything. Zhang Xiao’s aren’t mocking observations. Instead, I sense a mix of wonder, amusement and a little exasperation at the same time. It’s maybe the realization that this world has been moving a bit too fast and a bit too much, so things have become somewhat askew. Someone couldn’t bother, for whatever reason, to finish that bridge, or maybe there wasn’t the time, or it was simply forgotten because there was too much else to do. But someone is now paying attention, and this is what matters.

The lightness of touch with which the photographs in Coastline is presented is a most welcome counter point to the often dramatic, sweeping, overly pompous work made around China, especially by Westerners (lightness of touch providing a bit of a red thread in today’s reviews). There are a few pictures of whole cities that appear to be under construction, but there also is that woman sitting near the river, or a man in thought on a boat, a man lying on a beach glaring at the photographer, and much more. This is the China that interests me, the China I like seeing pictures of.

Coastline; photographs by Zhang Xiao; 192 pages, plus 16 folding pages; Jiazazhi Press; 2014

Rating: Photography 4, Book Concept 4, Edit 3, Production 3 – Overall 3.6

Paul Graham might be one of the few artists who have genuinely been pushing the boundaries of the medium photography in meaningful ways over the past few years, meaningful both concerning the push against photography’s restrictions and the end result. The same can be said about his publisher, MACK, maker of a flurry of exciting, if often a bit cerebral photobooks. However, this combination has now run into some serious trouble with Does Yellow Run Forever?, the latest book, which centers “upon the ephemeral question of what we seek and value in life – love, wealth, beauty, clear-eyed reality or an inner dream world?” (to use the publisher’s own words).

The book is an incredibly well packaged and produced object, as is usually the case with MACK. It’s modest, almost small, in size, fitting into the palm of a viewer’s hand. It has a soft, velvety cover. The book’s square is larger than is usually the case, leading to its pages – whose edges have a gold varnish on them – being hard to see when it’s closed (“The square of a book is the edge of its case that overhangs the text block” – source). The printing is luscious, with a glossy varnish on top of the photographs.

Unfortunately, the book’s production can’t hide the fact that its concept is, well, surprisingly weak. The publisher again: “The work weaves in and out of three groups of images: photographs of rainbows from Western Ireland, a sleeping dreamer, and gold stores in the United States.” Errm, OK, I get it. It’s just all a bit too obvious maybe, coming from an artist who has explored other themes in considerable more depth, offering more complexity.

Or maybe that’s not quite the right way to approach my problem with this book (just as an aside, I have only heard good things about the exhibition, which, alas, I haven’t seen). The problem with Does Yellow Run Forever? is that it’s trying too hard to be conceptually clever about a topic that simply does not survive being treated that way. There simply is too much weight here, too much of an attempt to make something profound for a topic that would have required an utmost lightness of touch.

If you want magic, you need to embrace that which makes magic magical. You can’t will it to happen.

I’m going to be forever in awe of a lot of this photographer’s work. But this book is a disappointment.

Does Yellow Run Forever?; photographs by Paul Graham; 96 pages; MACK; 2014

Rating: Photography 2, Book Concept 1, Edit 3, Production 5 – Overall 2.7

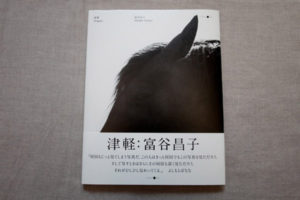

I was completely unaware of Masako Tomiya until her book Tsugaru arrived at my door step. This is not particularly unusual, since the world of Japanese photography is not very accessible to me (based on the conclusions of a panel I moderated at Unseen 2014, I should probably speak of Japanese photographers, given that one might not want to argue that there is a Japanese photography that is utterly distinct from, let’s say, Western photography). In many different ways, this is an ideal approach to photography: you don’t know anything about it, you can’t read the text that comes with it, all you have are the pictures.

At the risk of sounding simplistic and of infuriating those in the know, if you are curious what the photography looks like imagine a mix between Isssei Suda (let’s say, Waga-Tōkyō hyaku, a copy of the original 1979 version I am incredibly happy to own) and Rinko Kawauchi (let’s say, Illuminance). Much like the former, Tomiya works in black and white, focusing mostly on larger segments of the world, compared with the often myopic views presented by Kawauchi. But the photographic sensibilities on display are much closer to Kawauchi’s. There is that lightness of touch (that I have been speaking of before), a tranquility in the work that immediately grasps the viewer.

It’s a lightness with a bit of an edge, a lightness that, for me, makes me prefer these pictures over Kawauchi’s. It’s like the difference between reading a sentiment on a fortune cookie and having a genuine encounter with whatever might have been promised. You have to work hard on your photography to get to that point, where what is being described in your pictures (and there almost always is something that is being described) hints at something that cannot easily be talked about, is not being overly prescriptive.

Tsugaru mostly operates with pairs of photographs in any given spread, but not always. That’s one of my biggest beefs with Kawauchi’s Illuminance, where the simplicity of the pairings often has me exasperated. Tsugaru deftly manages to get around this challenge by offering mostly less openly resolved pairings and stand-alone images. There is none of the “this looks like that” that can make a photobook so tedious, especially when you realize that its subtitle might as well be “Why I am so clever”.

Printed beautifully, Tsugaru has become one of my favourite photobooks this year (even though it was released already in 2013).

Tsugaru; photographs by Masako Tomiya; essays by Kenji Takazawa and Masako Tomiya; 80 pages; Hakkoda; 2013

Rating: Photography 4.5, Book Concept 3, Edit 3, Production 5 – Overall 4.0

Ratings explained here.