There is something gratuitous about Ponte City, the book, that mirrors Ponte City, the apartment building that towers over Johannesburg. It literally towers, given it resembles a wide, inhabitable smokestack: a round structure, hollow inside, with windows all around (and inside) – a panopticon of sorts. It’s the kind of architecture that at some stage in the past made a lot of sense to those who commissioned and built it. Previously envisioned for those well off – white people in apartheid South Africa, Ponte City has now become a symbol for urban decay, standing – metaphorically – for all that ails the new, post-apartheid society.

Right around the time when developers attempted to “revitalize” the building, a term generously used when there is talk of gentrification, Mikhael Subotzky and Patrick Waterhouse went to Ponte City to document it, in the form of photographing every door and the view from every window. There are 54 floors and around 30 windows facing the outside (if my counting of a floor plan is correct), resulting in a lot of photographs. In addition, they collected discarded material from empty – abandoned – apartments.

There is a story here, even though it’s not quite clear what it is, given that however you want to look at it, you’re essentially not looking at one story, you’re looking at multiple ones. One could, conceivably, use the archive – the collection of the photographer’s images plus all the material they accumulated – to talk about vast parts of contemporary photography’s history, themes, and strategies. Abandoned apartments, with material left behind by those long gone; a ruin – or not quite ruin – of the past; the transition from one regime to another; immigration; wealth and the lack thereof… The list goes on.

How do you deal with this when you want to make a photobook?

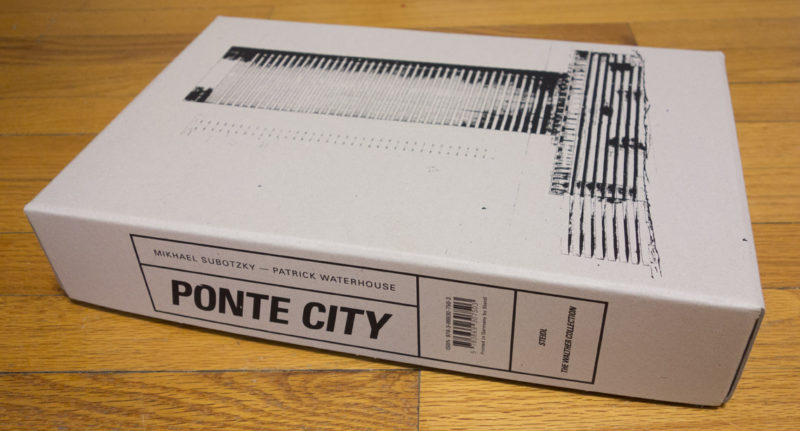

Depending on where you’re coming from, the solution picked for Ponte City is either the only one that does the material any justice, or it’s the equivalent of a baseball bunt (or both actually). The book isn’t a book, it’s a book in a box that also contains – wait for it – 17 separate booklets. The main book (sized 22cm by 34.5cm – 8.5″ by 13.5″) can – and does – easily serve as the core of the box. With the exception of various essays (each of which has its own booklet), most of the material is represented in some form in it, however briefly. The booklets themselves each focus on one particular aspect, be it an essay, or selections from the different types of materials.

I’ll admit that I have been – and probably will be – unable to make up my mind to what extent Ponte City is successful as a photobook (let’s be open to treating objects that consist of more than one book as photobooks as well). On some days, I think it’s just a brilliant way to throw back contemporary photography’s indecisiveness at those who can’t make their minds up where the medium is supposed to go, a brilliant way to do all the collected material at least some sort of justice. On other days, however, the sheer gratuitousness of the box bothers me. I get it, it’s a big building, and there’s a lot of material, but what is this supposed to tell me?

I suppose what this comes down to is my own struggle trying to deal with what essentially comes across as a refusal to go beyond a fractured authorship. It works very well, yet at the same time I’m itching for more – and by “more” I don’t mean more material, I mean more of a view point (which could easily mean a lot less material).

The box will undoubtedly appeal to those who value a well-produced smorgasbord (as, I’ll admit, I do). Steidl, the publisher, for sure knows how to produce a photobook. But then, where am I going to put this tombstone of an object in my library? Will it not, if found in a store or library or wherever else, intimidate some of the very people it is designed for? And will it not, to pick up a thread I wrote about recently, exclude some of the very people who might want to look at it, given they’re living in similar circumstances in places all over the world?

I realize this is the internet, so it’s likely people will just pick that one bit from the above that claims one thing, while ignoring all the others that do the opposite. Given you’ve made it this far into this review, if you read anywhere that I love or hate the box, you know that’s just baloney. I thought long and hard about how to possibly review this box to avoid just that situation – simplistic claims, supported by quotes taken out of context. But in the end, I decided to write the review that I feel had to be written. There’s no way of defeating those practices on the internet that so often make it almost unbearable.

Ponte City definitely is a photobook that deserves to be widely seen and carefully looked at, however much it makes exactly that harder than it maybe should have. Its presentation certainly is a very valid strategy to deal with a vast cache of material that will suffer when you reduce it down to something smaller, a vast cache of material that will offer a lot more with a lot less. The contradiction inherent in the material cannot easily be resolved, certainly not by me – it’s not my book, I’m merely reviewing it.

So in the spirit of its makers bunting over what to do with the material, I’m going to do the same with my rating. There’ll be two, one by the reviewer who’s in awe of the boldness of the venture (A), the other one by the reviewer who would have enjoyed to see more decisions (B). Recommended either way.

Ponte City; photographs and materials collected by Mikhael Subotzky and Patrick Waterhouse; essays by various authors; book plus 17 separate booklets; 192 pages; Steidl; 2014

Rating A: Photography 3, Book Concept 4, Edit 3, Production 5 – Overall 3.8

Rating B: Photography 3, Book Concept 2, Edit 1, Production 5 – Overall 3.0

Ratings explained here.