“These peculiar pictures of the everyday with their strange colour palette have invited my curiosity.” Conscientious Portofolio Competition juror Emma Bowkett said about Andrejs Strokins‘ photographs. “A wonderful, uneasy world, meticulously staged for the viewer to enter.” Indeed, there’s something strangely curious going on the world as this artist sees it. How and why I wanted to find out. I spoke with him over Skype — the conversation was subsequently edited for clarity.

Jörg Colberg: To start, can you talk about how you got into photography?

Andrejs Strokins: I was studying at Riga Building College to become a building contractor, after graduation I wanted to become an architect. To do that I had to pass exams, but I failed in mathematics. In the process of preparations I was blown away by drawing lessons in the art studio. It had different vibe. I really enjoyed hanging out there. So in the end these drawing lessons opened flood gates to the art world for me. At this point I got small digital camera from my parents aņd started to shoot a lot. It was in 2005, I think.

I continued to attend drawing lessons and as a bonus took one-year photography courses. The following year I went straight to the fine-art academy and got into the print-making department.

JC: From then on, you kept working as a photographer?

AS: Yes. It was a schizophrenic feeling. One part of me studied at the fine-art academy in a bohemian and carefree environment, while the other part was working in a photo-news agency. Doing art unrelated things.

By the way I made an awkward discovery today. An early press photo agency work is selling as an “art print” online. :)

AFI agency where I was working sold this image to European Press Photo agency, and from there it went viral. Here are a few examples.

JC: Is that what you do for a living, you work as a journalistic or commercial photographer?

AS: Yes, mostly commercial photography. Sometimes I’m still working in the reportage genre, but I don’t have the same feeling towards journalism in general. Besides I don’t get enough of those kinds of assignments to survive just doing journalism. So I’m doing more commercial jobs, but still I try not to go too far into commercial stuff. I try to do what feels right.

JC: But you do photography all the time, for yourself and your work?

AS: Yes. At some point, I quit the news agency because it was too much work. I didn’t have the time for my own things and my own development. So I just quit and started working as a freelancer, doing my own projects on the side.

JC: For your own projects, how do you approach them? How do you decide what to do?

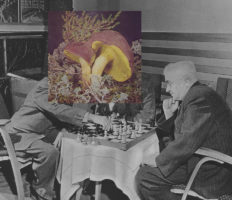

AS: With each project it’s different. I try to break my own rules all the time. I started with a classical documentary project about a district in a suburb of Riga. I’m still working on that. It’s called People in the Dunes. Since then, I have worked on different things. I’m also doing collages now, and I’m a quite passionate collector of found photography from my region, and Latvia. So I’m also doing some curatorial work related to that, making small exhibitions.

JC: What do you do with the found photographs?

AS: It depends on the specific archive or images. Sometimes, I’m playing with the context by putting a found image into my own work, trying to shift a viewer’s perceptions of what he sees in the image in a bigger sequence of pictures.

I’m really interested in amateur photography, how amateurs approach photography and what they photograph. Sometimes, they find really interesting approaches and make art unintentionally. Quite recently I started to collect also amateur photo albums.

JC: So you have all these photographs, the vernacular photographs, your own projects. What’s the end product (I know that’s an ugly word)? Do you make books, do you make exhibitions?

AS: Mostly exhibitions. I really want to make a book, at least for one project. But it’s really a slow process, and I’m trying to think and re-think and again and again… I have this fear of failure towards bookmaking. But surely it will happen at some point. It’s a more complicated process that I have to “study first, then do”. I’m fine with making exhibitions for now.

JC: Latvia is a relatively small country. How many galleries do you have?

AS: None photography related.

JC: So are you looking for galleries outside of Latvia?

AS: Yes and no.

The best way how to describe my feelings lies in this quote “You’re a struggling artist who doesn’t care about money or fame but really you care about money and fame, but you don’t care about money or fame.”

One the one hand, you’re not doing this because of money. But on the other hand, of course you want to make money from what you’re doing. I would like to spend more time on doing art than doing commercial work. I don’t know, I don’t have the energy to sell my images or to look for someone to sell my images. I don’t have the energy for all the business aspects. Maybe I need agent or manager, but then again I don’t have energy for that.

JC: Maybe we can talk a little bit about your project that won the competition. It was called Everyday Error at some stage, but you changed the title?

AS: Yes hashtag on Instagram, #everydayerror still remained, but I have changed the title of the project to Cosmic Sadness. I often change things. The title Everyday Error and the whole project was inspired by Milton Glaser’s online lecture called “on the fear of failure”.

JC: These are pictures that you photographed with your smartphone, using a custom-made filter?

AS: Yes. That’s quite easy to do. I use this Android app called Vignette. This app allows you to change filters and adapt them to your needs. So I did that. It’s another project, another rule. I put myself into this box where I’m shooting vertically with this specific filter and a 4×5 aspect ratio. And that’s it. I’m not thinking about postproduction. I’m simply snapping images. I have to admit that I really like this process.

JC: Do you often work with rules for your projects?

AS: Yes. It’s a game, you know. You put yourself into box just to see what will grow from it.

JC: Tell me a little bit more about what you do in this project. You walk around, and you take pictures with your phone?

AS: I take pictures when environment resonates with me and fits the game rule set that I have invented. Mainly it is a bitter/sweet melancholic dive into my personality.

JC: Is this an open-ended idea that you will continue for a long period of time?

AS: Actually, I don’t know, because it’s related to technology. We has to see how the technology will evolve. Every year, companies are throwing new smartphones with better cameras and new inventions. These cameras has different visual qualities and aesthetics. My mobile phone represents lo-fi digital photography with tiny nostalgia to analog film era. It would look completely different with a new generations of mobile phones. So maybe I will switch to something else. But I think I will still have something in my pocket to document whatever will find. That’s for sure.

JC: For every artist, there’s the question of “why am I doing this?” or maybe “what am I doing this for?”. What do you think about these questions? What you do is that for exhibitions, or is it to satisfy your own curiosity, to see what the world looks like in these specific ways, given your rules?

AS: There is no reason for anything, but in my case I think it’s curiosity – a specific way to deal with reality. Other things just comes along.

My parents told me once that on my first school day in first grade I was watering flowers while the others were sitting and listening to what teachers had to say. I have feeling that I am still watering those flowers while others are doing more proper and meaningful things.

You know… I am a shy person and it is hard for me to communicate with strangers on casual level.

Recently, I was at an exhibition opening, and I wasn’t photographing. I was part of group of elite artists and invited guests who were there just to hang out. I felt so weird without my camera, without a purpose. I didn’t know how to approach people.

When you have a camera, you always take photographs, and you are there in the moment, but you don’t have to interact with others. I think the camera is my escape mechanism from society. But at the same time it’s a way to integrate with it.