Some time last year, I found a copy of Abigail Heyman‘s Growing up Female in a local second-hand book shop. I ended up writing a little piece about the whole experience, and I eventually included the book in the list of my favourite photobooks last year. As much as I enjoyed the book, there was a slight problem, though. The glue holding it together had become very brittle with time, and it had cracked, leaving at least one page dangling quite badly.

Yesterday, I asked a bookbinder friend of mine whether he could re-glue it. I felt kind of bad about asking, though, not because of the favour, but because I could have just bought another copy online, hoping to get one that wasn’t broken. Back when I bought the book (paying $6.00) there were copies listed for as little as $0.75 online. My friend told me he didn’t mind fixing it all, but I went online to see what my options were. Turns out prices for the book have gone up, the cheapest copies are now starting around $11 for both the hard and softcover versions.

I have no way of knowing whether my writing about the book had people buy up the cheap copies. In some sense – whether I have in fact that kind of influence, it doesn’t matter to me. In another sense, it does, though: here was a truly wonderful photobook that was (and still is) incredibly relevant, and you could have it for the equivalent of whatever it is that these days costs $0.75. Something truly didn’t feel right about that.

Photobooks are commonly discussed, especially since the books about photobooks industry started to take off. There are many reasons why those kinds of books are doing the community a huge favour. After all, not only do they discuss the medium photobook in ways that it truly deserves, they also expose a lot of unknown books to a larger audience. Except, of course, that often enough you then see those books listed on Ebay, say, with, for example, “Parr/Badger” included in the subject line.

You know what, I don’t really care about that aspect of the photobook market that much. OK, there might be the occasional book that I would really love to have in my library, and that I cannot even remotely afford (think Michael Schmidt’s Waffenruhe). But the reality also is that for every Waffenruhe there are dozens of other books that you can buy for next to nothing, many of them genuinely good. It doesn’t take much to get these books. All you have to do is to look for them, and you then buy a book that you like (even if you have never heard any of the usual suspects talk about it).

There’s an essay in Gerry Badger‘s marvelous The Pleasures of Good Photographs that talks at length about a large number of female photographers that have simply — so far — been excluded from what we think of as our standard history of photography (“From Diane Arbus to Cindy Sherman: A Exhibition Proposal,” p. 199). I don’t think Heyman is mentioned in Badger’s piece, but it would be straightforward to think of her of one of those who Badger talks about. Seen that way, many of those photobooks that can be had for next to nothing online or in second-hand book shops can also serve as a corrective to photography’s history (or maybe rather the way it was written).

This is not to say that every photobook that appears to have been forgotten is a masterpiece — just like many of the books in, say, Parr and Badger’s series are, well, really not that great at all. But, and this is quite important, the exhibitions that happened in the 1970s — they’re all gone, inaccessible. The same is true for the prints people might have made, which, with a little luck, languish in some museum’s collection (rarely to be seen) or hang in someone’s home.

But the books made during that time, in fact during pretty much any time, are still around. Even though considerable (now mostly virtual) ink is being spilled on a relatively small set of books, most books have become those incredibly cheap photobooks that you can swoop up on Amazon or maybe Ebay for next to nothing and that, with a little luck, you can find in your friendly second-hand book shop for a little — but not much — more.

This is one of the reasons why I love photobooks so much. The kind of access they give me to photography is so much larger than what I can have any other way. I realize that providing examples might ultimately defeat the purpose completely: what if people start buying all these books, for prices to shoot up into the stratosphere? But then, is it fair to a book and its author to simply not mention it just so that it remains cheap, and someone might find it being as lucky as I was? Now that I finally decided to write this piece you can probably guess which side I have come down on.

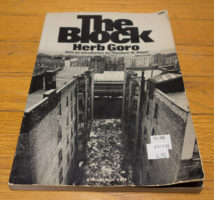

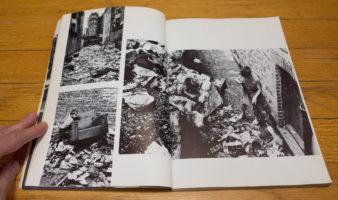

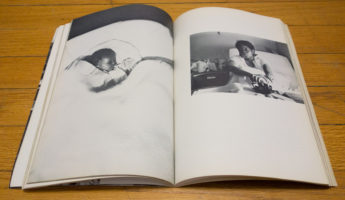

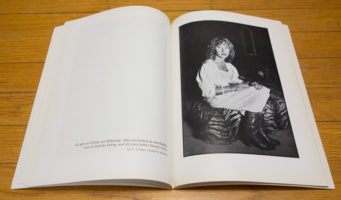

Btw, Heyman’s book is being repaired right now, so I’m unable to show you any spreads. But I’m including a few other lucky finds here.